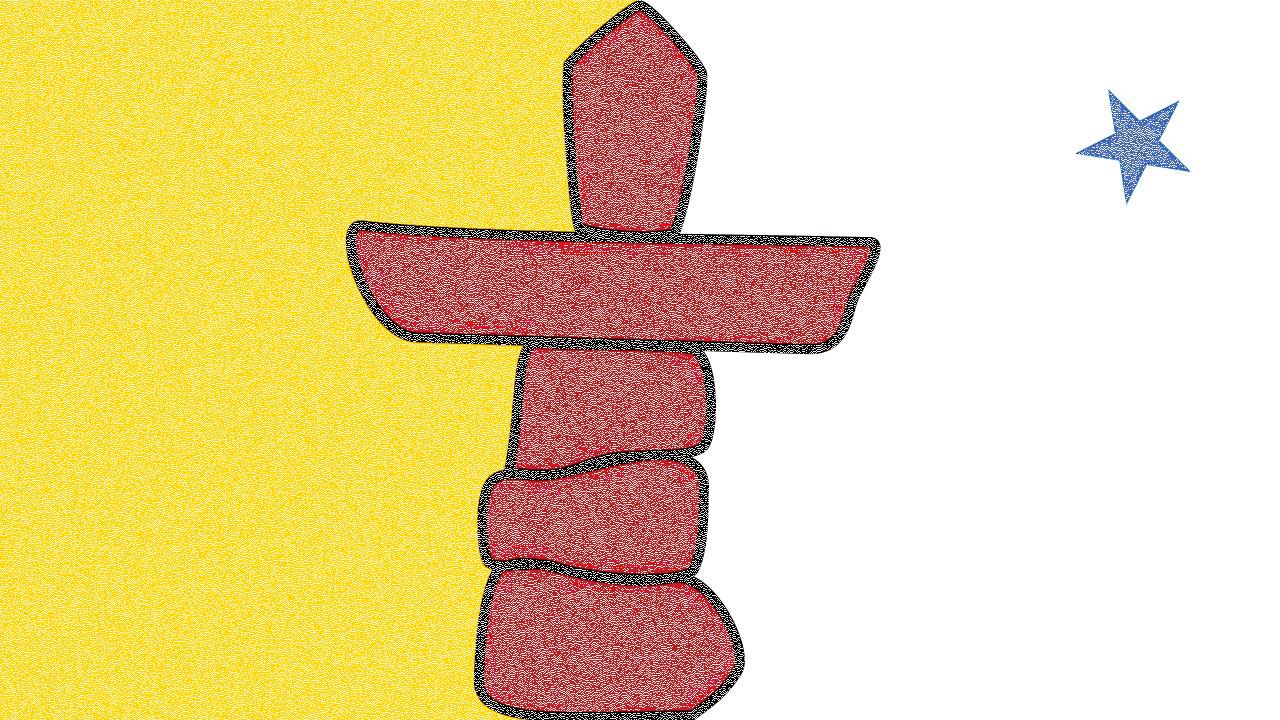

Nunavut

Our Land

In the year 14, the Roman senate passed a law making it illegal for men to wear silk. Silk was insanely expensive, coming as it did from Serika, the Land of Silk, over 4,000 miles away, but it was just the thing to wear in a warm place such as Rome. As a result, it was so very precious that it was routinely unraveled when it arrived and rewoven to be gossamer-thin, to the point that it was essentially transparent. This was considered the height of fashion for Roman women, but absolutely no one wanted to see a Roman senator clothed in such a manner, and hence the new law banning the wearing of the material by men.

By the time the senate passed their new silk law, the material had already been around for thousands of years. It was invented by the Yangshao people sometime in the fourth millennium BCE - in broad strokes you boil the cocoons of a certain worm, killing the worm before it can bite its way out. Then you unravel the silk and re-ravel it into a garment. The new garments quickly caught on, and the silk trade extended to Korea, the Japans and the Indian subcontinent almost overnight. A Siberian mummy dating from the first millennium BCE was buried in a silk garment, indicating that the silk trade had progressed quite a bit north. An Egyptian mummy, too, was buried with silk, showing that trade had extended to the west. But it was when Marcus Licinius Crassus, the Roman governor of Syria in 53 BCE, saw the beauty of the Parthian banners, which were made of silk, that the new (to Romans) material found its real market.

Now you have to understand that ancient Geography was a little hazy. So Serika, then Cathay, then China and finally The Indies, were sort of general terms for the Orient (the east) as opposed to the Occident (the west). And so Serika was the presumed source for a lot of things besides just silk. Spices too, and rare and beautiful works of art; strange animals; stranger ideas, and even deadly diseases were flowing west, while glassware, exquisite cloth, coins and the pax Romana were flowing east. But it wasn't like any one caravan bought stuff in Chang'an, travelled for between one and four years through deserts and mountains and bandits and then sold it in Byzantium; there were any number of intermediary stops in between all taking their percentage and any one stop only knew about the next one down the line. So while Rome and Serika were dimly aware of each other, the Persians, Kushans and Byzantines in between were the ones truly in the know. And they were making so very, very much money from the caravans travelling through their lands that they took it upon themselves to dissuade the powerful Romans and Hans from sending emissaries to each other. Because the land route between the two empires wasn't the only way to go.

The funny thing about the Indian Ocean is that the monsoon winds always blow from the northeast in winter, reversing direction to blow from the southwest in summer. So if the silks and spices and what-have-you could make it by land as far as the Indian subcontinent then one could cut the silk road in half by transporting goods from there to Rome by ship, in exactly one year round trip, with absolutely no camels involved. Except for a bit of a portage in the middle where the Suez canal would be one day. This is exactly what a Greek sea captain by the name of Hippalus discovered in the first century BCE and by the reign of Caesar Augustus there were 120 Roman ships every year making the trek to Scythia, Ariaca and Dakinabades (northern, central and southern India) to trade for all things Oriental.

The Roman Empire was at its height around 117 AD but then pretty much entirely disappeared 350 years later, and the Italian Peninsula fractured into several city-states and short lived Kingdoms. But by the latter part of the 15th Century, several of the city-states had emerged as dominant maritime republics. These included Venice, Genoa, Amalfi and Pisa. And they were all very much interested in continuing the monopoly on trade to the Indies that Italy had enjoyed for the better part of two thousand years. But the republics really only succeeded in training a generation of highly skilled explorers: men like Cristoforo Colombo, Amerigo Vespucci, Giovanni da Verrazzano and Giovanni Caboto (whom we'll talk more about shortly). And these men all realized they didn't necessarily have to work for a city-state. They could work for people like the Portuguese, who had a much bigger budget. And who also wanted very much to trade with the Orient.

But trade with Cathay for a place such as Portugal involved a lot of issues. The Italians had the monopoly on this end of the silk roads (land and sea) and the Ottomans had the monopoly in the middle. And that meant money and random border closings. All of the little places between the Ottomans and the Chinese had lesser monopolies, depending upon how far your camel could walk or your dhow or junk or whatever could sail before needing supplies. These little empires too would take whatever cut they could get. And the worst problem was China itself. It had just evolved from the Hans to the Mings, and the emperors in between had been randomly closing the borders to trade and executing all foreigners. The Mings had largely sorted that little problem out by 1368, although even they were not really fond of foreigners. This would eventually lead to "quarantine" cities like Macau, but that's getting a little ahead of ourselves.

In the meantime, Portugal needed a sea route directly between Iberia and Asia, one that bypassed the Italians, the Ottomans, and all of the other little kingdoms thereafter (at least until they could be subjugated). And one that didn't have that little portage in the middle, between the Red and Mediterranean Seas. People such as Alvide da Ca' da Mosto, a Venetian explorer in Portugal's employ, had been exploring and mapping the west coast of Africa since 1455, and that looked promising. So in 1488, Bartolomeu Dias continued those explorations, sailing down the western coast of África, around the Cabo das Tormentas, the Cape of Storms, aptly named because the meeting of the warmer Agulhas current with the colder Benguela current made for some lively adventures. Once on the far side of what would become Cape Town, it was relatively clear sailing under the bottom of África and then onwards to the Indian Ocean, which was previously thought to be separate and inaccessible from the Atlantic. But even with that proven route it would still be ten years before Vasco da Gama made it all the way to Calicut in India, where he set about creating factories and trading for things such as pepper.

About this time England decided to get into the game. But Henry VII, the first Tudor King of England and Lord of Ireland, had to tread softly, because a naval power he was not. Nor any kind of power really, outside of England and Ireland. The proven way south around the Portuguese Cape of Storms and then on to the Orient to the east would for sure involve a confrontation with a vastly superior navy. But speculation had it the world was round, so Henry sent a venetian named Zuan to go check out rumours of a new land far to the west, which might itself be China, or would in any case certainly lead there.

Giovanni "Zuan" Caboto had many names and more spellings, as the custom in his day was for people to italicize, gallicize, iberianize or in this case anglicize the names of anyone they had dealings with. So it was John Cabot (and his son Sebastian) who sailed from England in the latter part of the 15th century to explore the new lands to the west. His goal was to find a north west route to the Orient, bypassing Portuguese and Spanish held lands to the south west.

Not much is known for certain of his voyages, even the dates of them, because the whole world outside of Europe was then owned jointly between Portugal and Spain, according to the Doctrine of Discovery, which essentially said that all non-Christian lands were uninhabited and the first people to sail there owned them, especially if you were either Portuguese or Spanish. They had decided that the half of the world this side of the 46th meridian was Portuguese territory, and anything past that was Spanish. At the time, that meant that Portugal owned the entire known world and Spain could have everything else. It soon came to mean that Portugal owned the nub of South America to be known as Brasil and Spain owned everything else in the New World, but that is part of another story. In the meantime, rather than cause an incident with the global super powers, the notes of Zuan's expeditions were kept a little vague and even the dates were doctored so as not to conflict with the Treaty of Tordesillas and the Iberian monopoly.

His first voyage was officially an abort; whatever really happened, it was recorded as a turnabout and head home without finding anything. His second voyage, which likely took place four years after the official date, was also a total failure because John did not find China. But he did discover a new land. John was given £10 as a reward for discovering the New Founde Lande, which was later upped to £20 a year, but more importantly, he received letters patent for a much larger voyage to see what could be made of this place.

This next trip, John's third (and last), had five ships, all laden with trade goods. Which somewhat calls into question John's assertion that he had not really gone ashore in his previous voyages nor met anyone. They also took some priests, also somewhat odd if you didn't expect to meet anyone. In any event, it's clear they made it as far as Ireland because one of the ships only made it that far, but the rest sailed on; into the fog of history, taking John Cabot with them. Some say he returned to England in 1500; others say the expedition founded a Christian colony on the Avalon Peninsula in the New Founde Lande named Carbonear (after the friar Giovanni Antonio de Carbonariis who was a part of the expedition and reputedly built a church there). Others say Cabot simply vanished.

But whether or not Cabot did in fact vanish, King Henry had other irons in the fire. He sent other, increasingly more serious expeditions to see if this new island would lead to the Orient. William Weston sailed up the Hudson Strait (a later name) in 1499, becoming the first true explorer of the Northwest Passage. Hugh Eliot and Robert Thorne also mounted expeditions to the Isle of New Finding; these were so well funded that they created the Company of Adventurers to the New Found Land so their endeavours could survive any misfortunes that would end a private concern. Even John's son, Sebastian Cabot, returned to the Isle. But by the time Sebastian returned to England he found that Henry VII had passed the crown on to his son, Henry VIII, whose attention was focused on France.

The new Henry, Henry the Eighth, by the Grace of God, King of England and France, Defender of the Faith and Lord of Ireland, actually only had the one territory left in France: Calais. He was after getting Aquitaine back, and eventually, all of France. To this end he became fast friends with Louis XII, the other King of France, while simultaneously double-dealing against him with Spain, in order to mount a combined invasion while France's attention was upon their own invasion of Venice. So Henry VIII had enough intrigue at home and therefore little time for discoveries in the New World. The English quest for a passage to China in the north west therefore hit a bit of an iceberg.

So back to the Portuguese. In 1522, Fernão de Magalhães, or Ferdinand Magellan, did not return home from an expedition he had planned and led to the Spice Islands in Asia. But one of his ships did, and they reported that Ferdinand had discovered a navigable route through the bottom part of South America which led them ultimately to China and thence home to Spain from the wrong direction. So it appeared that the world was in fact round, and there were now two different, equally dangerous ways to get a ship to China and back.

Thusly Portugal acquired the monopoly on Asian trade, having successfully taken it from the Italians, using their much superior shipping routes instead of the unreliable overland routes or ocean routes involving a portage. The Portuguese were receiving silks, of course; but also cotton, tea, porcelain, ivory and other luxury goods like spices. Spices at the time were the ultimate luxury item, reputed to have various health benefits, which to a small degree was true: cloves, for instance, cure toothache. But really, spices were just a snobby thing to have in your recipes that poor people couldn't afford.

It's kind of an historical urban legend that black pepper was worth its weight in gold in medieval Europe, important for the common folk to preserve and cover the taste of meat that had gone off. The reality is that common folk did not routinely eat meat, no matter its state of composition. And if they did, they knew that the best ways of preserving meat were on the hoof, in one's belly or heavily salted. Pepper does not preserve meat. As for its cost: when the silk law came into effect in Rome, one could buy a pound of black pepper for four days' wages. Not something you were likely to do if you were living denarius to denarius, but far from the cost of gold. By the time Portugal got into the game the price of a pound of black pepper had fallen to a little over two days' wages, not out of reach of the common folk, but they likely had other things to reach for first. So spices, and pretty much everything else that came out of the Orient, were luxuries for the wealthy. Which ensured a steady market and prompted more countries to join in.

Like Spain of course. Spain and Portugal were kind of joined at the hip in those days through the Treaty of Tordesillas, and the subsequent Treaty of Saragossa which defined the anti-meridian for the first treaty (the world being round and all) so it was not surprising that Spain would get involved. It was a player mostly in the Philippines (named after Philip II of Spain), which was probably outside of Portuguese territory; you really can't accurately tell where any particular meridian is without a clock. In any event, Spanish colonists living in Manila would collect riches from the Orient such as wax, silk of course, gunpowder, and all of the other things you got in the east. Then twice a year a Manila Galleon would arrive from Acapulco loaded with silver to exchange for cargo. On returning to Acapulco on the Pacific, the cargo would be loaded up onto a mule train to make the trek, along the China Road, to Veracruz in the Caribbean, where a Spanish treasure galleon would complete the journey home.

It was about this time that the French decided to get into the game. In 1535 things were relatively peaceful between France and England; Henry had just enlisted the aid of King Francis to marry Anne Boleyn, and he was otherwise busy with the Pope. So with the temporary peace, Francis sent Jaques Cartier west to explore "certain islands and lands where it is said there must be great quantities of gold and other riches", which pretty much had to be China. Jaques sailed up the Saint Lawrence, which seemed to be headed in the right direction, and made it about half way to China before being stopped by the Lachine (China) Rapids at present-day Montréal. While they hadn't found the route to Cathay, Jaques and his party had certainly found a land containing great quantities of riches. So the French turned their attention to this new land and while they were always open to finding the passage to the east by going west, there weren't any determined efforts in that direction for a time.

So back to England. Henry VIII had passed the crown on to his son, who became King Edward VI at the age of nine. The realm was really being ruled by 16 executors, and they in turn were ruled by Edward Seymour, 1st Earl of Hertford. There's a bit more to that story, but the upshot is conditions were ripe for business ventures and so the Mystery and Company of Merchant Adventurers for the Discovery of Regions, Dominions, Islands, and Places Unknown, also known as the Company of Merchant Adventurers to New Lands, or simply the Muscovy Company came into being. Their primary consideration was trade with Muscovy (Tsarist Russia) rather than China. So in 1553, Hugh Willoughby set sail to discover the North East passage. That expedition was itself discovered a few years later in Murmansk by fishermen, stuck in sea ice but otherwise alright - they had lots of provisions and a huge supply of "sea" coal from a nearby bay. None of them appeared to be injured in any way, other than being frozen solid. It is likely they died of carbon monoxide poisoning.

A little bit later, in 1576, Martin Frobisher approached the Muscovy Company to underwrite his expedition to search for a route to Cathay by way of the Isle of New Finding. Martin was a nasty man, but for today's story we'll just talk about his search for the North West Passage. He was something of a cult hero; as his expedition headed down the Thames past Greenwich Palace, Queen Elizabeth, who was single and had "good likings of their doings", waved from a window. There was a cannon salute and so of course the small folk turned up to see what was happening. On this voyage, Frobisher discovered Frobisher's Strait, clearly the entrance to the fabled passage. He also discovered a large black rock, which he took home as a token of his having discovered the Meta Incognita (Unknown Shore - later known as Baffin Island).

It turns out the black rock was marcasite, somewhat worthless although pretty enough. That is, most assayers said it was marcasite. One, however, a bit of an alchemist, said it contained gold; it was on his word that a much, much bigger expedition, this one underwritten by the brand new Cathay Company, went back to the Meta Incognita. Frobisher was specifically instructed by the venturers of the company not to explore anything, just bring back rock. This he did, returning with over 200 tons of the black rock, along with three kidnapped Inuit who all died shortly after arriving at England, at least one from injuries sustained during his capture.

While the royal smelterers were trying to figure out what to do with 200 tons of costume jewellery, Frobisher again set out, this time loaded for bear. He had 147 miners, 4 blacksmiths and even 5 assayers amongst his fifteen ships and 400 men; everything necessary for the making of a semi-permanent mining camp. On July 2nd, 1578, they again sighted Frobisher's Strait, which would later be found to be Frobisher Bay, but were blown off course to Mistaken Strait, later to become Hudson Strait. They followed this new strait for a good sixty miles, almost making exploration history, before deciding to turn back and get to work on the mining camp.

The camp was an utter failure. Elizabethan prisoners and miners conscripted into a voyage to the far north, it turned out, were ill-equipped to survive the extremes of weather to be found there. But the venture itself seemed to be a success. Huge amounts of ore were sent back to England, where it was discovered to be Horneblende, in no way gold bearing but absolutely perfect for gravelling roadways. The Cathay Company went bankrupt; the man behind the scheme went to debtor's prison, and Frobisher went on to become a notorious scallywag who nonetheless knew upon which side his toast was buttered, and he was knighted for confining his ill deeds to the Spanish Armada.

While all of this was going on, the Dutch were becoming a power. The Burgundian Netherlands were a collection of fiefs which became the Seventeen Provinces (of Habsburg Spain). Spain, of course, was violently Catholic and didn't treat the people of the Reformation all that well. So the Protestants of the Low Countries revolted against their foreign Catholic occupiers in 1566. Seven of the northernmost provinces formed a republic, much to the annoyance of Iberia. In order to distract everyone's attention from the issues closer to home, the rebels decided to attack Iberian shipping routes. We'll talk about that and their conquest of Malacca another day. For today we'll just say that in 1609 the Vereenigde Oost Indische Compagnie (Dutch East India Company) hired an English navigator by the name of Hendrick Hudson to continue his earlier efforts on behalf of the Muscovy Company in the search for the North East Passage above Muscovy and into the Northern Pacific.

Just like in his previous two attempts, Hudson was blocked by ice. This time, though, rather than turn around for home he decided to ignore his mandate and look west. He put in at a Mi'kmaq village near the future site of Mirliguèche in what would become Nova Scotia, and took on provisions, killed or drove off all the locals, and stole all of their stuff. He then went on to explore the river that now bears his name, which turned out not to be a route to the Pacific but nonetheless gave the Dutch a claim to the New World and its furs.

A year later, Henry (as he was known in England) approached the Virginia Company and the British East India Company for funding to try again, this time to the north of the New Founde Lande. On 25 June, 1610, Hudson and his crew aboard the Discovery entered the Hudson Strait, and a month or so later, Hudson's Bay. They spent the time until freeze up looking for the Northwest passage, which they continued in the spring after overwintering in James Bay. But overwintering in James Bay is not for the average Englishman; looking forward to another year of a fruitless search for the passage followed by a brutal winter, the crew mutinied and set Hudson, his son, and those loyal to him, adrift. Hudson was never seen again, and the crew, upon returning to England, was tried for mutiny and then promptly acquitted; they and their knowledge of the northern waters were too valuable to hang. The very next year the Discovery and even some of the mutinous crew were back searching for the passage.

That particular voyage returned prematurely when the crew got sick, but the next year the Discovery was off again, this time with a pilot by the name of William Baffin. With Baffin calling the shots, the search was a little more methodical than previous efforts. They sailed so far north that their record wasn't broken for almost a quarter of a millennium. They mapped (and named) many islands, bays and sounds, and more or less put the whole idea of an ice-free passage to the Pacific via the New Founde Lande to bed, where it remained for over two hundred years as far as the English were concerned.

During that time, there were of course still efforts to find the passage, by other countries and from other directions. The Danish sent an ill-fated expedition to overwinter at the mouth of the Churchill River; three of them made it home. René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, built the barque Le Griffon upstream of the Sault Saint-Louis (previously, and currently, the Lachine Rapids) and sailed it all the way to Lake Michigan. From there he succeeded in finding a navigable route to the ocean, unfortunately the Gulf of Mexico and not the Pacific.

On the Pacific side, the Danish, the Russians, the Spanish, and most notably the English, were all looking for a route from that direction. None of them found the passage, but what they did do was map everything on that side sufficiently well that by 1845 it was known there was only a little over 250 nautical miles of unknown in the middle of the maps, separating the Atlantic from the Pacific. So Sir John Franklin set out with two ships, the Erebus, 378 tons berthen, and the Terror, at 331. Both ships had steam engines so they could make four knots even without wind. They had reinforced bows to withstand ice. They had steam heat. They had over three years' supply of food, including many live cattle. Their libraries contained a thousand books. They could retract their rudders and propellers to prevent ice damage. Even so, they disappeared in the high arctic, near King William Island in the Arctic Territory, sometime in 1846. It is possible they slowly went mad from lead poisoning - the order for 8,000 tins of food only reached the supplier seven weeks before they set sail, so some of the soldering was "thick and sloppily done, and dripped like melted candle wax down the inside surface". In any event, the expedition disappeared.

Sir John's wife, Lady Franklin, did not take her husband's disapearance well, and continually pushed for rescue missions to find him. These searches would ultimately succeed in finding the Franklin Expedition, but, sadly, not until 2014, more than a hundred and sixty-four years after it is likely the last of them died. But there was a more timely result of the expeditions: the successful traverse of the North West Passage.

In 1854, Robert McClure set out in the HMS Investigator looking for Franklin. He decided to search from the west, in case Franklin made it that far. McClure and his party got as far as Mercy Bay on Banks Island, present-day NorthWest Territories. There they were trapped in sea ice for three years. Just as the food ran out (maybe a little bit after it ran out) they were, incredibly, rescued by a sledge team from the Belcher Expedition, which was also looking for Franklin and by this time for McClure as well. Belcher had been searching from the east, and had made it to Melville Island, present-day Nunavut, and about 150 nautical miles from Mercy Bay, before becoming himself stuck in sea ice. It would take another year, but eventually Belcher and McClure made it back to England, McClure being technically the first person to traverse the NorthWest Passage.

But some would argue that a route between the two oceans that involved a sledge in the middle didn't count. Which brings us to Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen. He was first mate aboard the Belgian Antarctic Expedition from 1897-1899. The Beligica was not well provisioned, and that became an issue when they got stuck in sea ice for a year off Alexander Island. Scurvy was the likely result of being stuck in sea ice without enough provisions, a horrible way to die. But the ship's doctor made everyone eat raw animals. Most animals produce their own vitamin C, it's really only monkeys and apes that do not (and bats and guinea pigs). So if you eat raw meat containing vitamin C you don't get scurvy.

This is a well known fact amongst the Nestsilik Inuit of the high arctic of the land that would become Nunavut. So when Roald decided to try the NorthWest Passage in 1903 he spent two years stuck in sea ice on purpose in a little Nestsilik community that would aquire the name Gjoa Haven, after Roald's ship, a small herring boat called the Gjøa. There, he and his five crew learned how to survive in the high arctic from the people that had been doing it for thousands of years. Because Roald intended to attempt the passage in a whole new way. Where previous attempts such as Franklin's battled against nature, throwing technology and money at the problem, and not interacting to any great degree with the local Inuit (other than maybe kidnapping them), Roald decided to work with nature, and in particular the Inuit. He kept everything low-key and above all small. The Gjøa was only 45 tons berthen, and had a draft of only three feet, making many routes available to him that were impossible for the larger expeditions. So he and all of his crew arrived in Nome, Alaska in 1906, having traversed the passage from east to west, and the only drama of the entire voyage was the discovery that there was no way of telling anyone about his success. So he skied 500 miles inland to Eagle, a bustling Klondike Gold Rush town, to send a telegram. Then 500 miles back again.

So after almost two thousand years, a navigable route to the Pacific Ocean and thence to Cathay was proven to exist through the Arctic Territory, later to be called Nunavut (for most of the passage). Admittedly, the route required that you had two years' experience surviving the high arctic and a boat of less than three feet of draft. So maybe not really commercially practical, but we'll talk more about that tomorrow.

A much more practical use for the arctic, especially the low arctic around Baffin Island, was whaling. But anyone who went there had to ensure they left well before freezeup, or they were likely to find themselves frozen in Frobisher Bay.