Churchill

Polar Bear Capital of the World

Thousands of years ago, a man named Noah (after Noach, or possibly Nukhu, Hebrew and Babylonian respectively for rest or repose) survived a flood of literally biblical proportions that was sent by God to cleanse the creation of wickedness. Noah survived the flood in a large ark (barge) with his family, and between two and seven of every kind of animal and bird. The ark came to rest on Mount Ararat, on the border of present-day Turkey and Armenia, and Noah sent out a raven and two doves to report back. One of the doves returned with an olive branch, telling Noah that it was ok to go ashore. God then created a rainbow as a pledge to never again destroy the earth with a flood. Thereafter Noah became an husbandman (farmer) and set about growing grapes for wine.

Meanwhile, in ancient Greece, a man named Deucalion was warned by Zeuss and Poseidon about the flood. He also decided to build an ark and fill it with critters. When the flood subsided, he sent out a pigeon to see what was happening, and that bird also returned with an olive branch. After the land dried up, Deucalion then became a farmer and invented wine, since that was the thing to do after a flood.

Around the same time, the gods of Mesopotamia decided to send their great flood to destroy mankind. The hero of this story was a man named Gilgamesh who built an ark, loaded it with animals, birds and family, and waited out the flood.

In ancient Sumeria it was Enlil, the deity of Wind, Air, Earth and Storms who decided to destroy the earth with a flood, and Enki, the god of Water, who saves man. In ancient Norse mythology, the blood of Ymir, the first Frost Giant, floods the earth after Odin and his brothers kill him. Luckily, Bergilmir escapes with his wife in a lúðr (a wooden box) to repopulate the earth (with Frost Giants). Further afield, a man named Manu was warned by a fish that a flood would destroy all of humanity, so he built a boat and the fish steered him to safety upon a mountaintop. And really far afield, a man named Nu'u also built an ark to escape his flood. That ark came to rest atop mount Mauna Kea, in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. After that, Kāne, the creator god, descended to earth on a rainbow to talk about Nu'u's sins.

In Canada, or, more accurately, the Ojibwe nation, Nanabozho angered the Great Serpent sufficiently that he settled to the bottom of the lake he inhabited and began to agitate the waters, so as to drown Turtle Island and all of its inhabitants. Nanabozho ran before the angry waters shouting for his children to flee to the mountain tops, where he made a raft and saved all of the people as well as their animals.

These are a few of the dozens upon dozens of stories about a major flood in antiquity, to be found in every civilization and corner of the world. But these are just the stories that have survived. There are likely to be many more that have not survived, because the civilizations who told the stories themselves did not survive, possibly as a result of some kind of flood. Now, whatever you might think about any individual story, as a whole you have to start taking them seriously. The consensus amongst them seems to be that there was a global extinction event, a flood; some people and animals escaped in a boat; afterwards, people became farmers, especially those living in the middle east, the Fertile Crescent. The message in all of the stories is clear: you cannot count on the weather. Now let's apply some conjecture to that message.

Approximately 10,000 years ago, the Wisconsin Glaciation, the latest in the series of glaciations of the Quaternary Period, was ebbing towards the interglacial period in which we now find ourselves. Canada was still pretty much covered by the Laurentide Ice Sheet, although that was melting and becoming some pretty impressive, you might even say great, lakes. Just south of the retreating ice sheet, the huge Lake Agassiz was merging with the even bigger Lake Ojibway to become a lake of unimaginable proportions, running 1,500 km from what would become Reindeer Lake in Saskatchewan (after things dried up a bit) all the way to Lake Mistassini in Québec, all meltwater compliments of the ice sheet.

But the Laurentide hadn't totally melted yet. At its maximum, the ice sheet was perhaps three kilometers thick in the middle, and that would have been directly over what would one day become Hudson's Bay. Ice weighs around a ton per square meter, about a billion tons per cubic kilometer. So the ice had enough weight to actually bend the land under it. The basin of Hudson's Bay was a half a kilometer lower in those days than it is now, due to the unimaginable weight of cubic kilometers of ice above it. And as the ice sheet retreated north, this basin would have filled up with an inconceivable amount of fresh water that drained as best it could to the south and the east, but was largely being held in place by a big chunk of ice to the north. Now hold that thought for a moment; back to the middle east.

Çatalhöyük, fork mound, was an ancient Neolithic (new stone-age) settlement in modern-day Anatolia, Turkey. It was a thriving city of thousands of people between 7,000 BC and its sudden abandonment six hundred years later. It is significant because it was one of the very first fixed communities, and represents a quantum shift in how people lived. Prior to this, in the Paleolithic (old stone-age) and Mesolithic (middle stone-age) periods, people lived in nomadic or semi-nomadic groups of largely inter-related people, hunting and gathering and moving about as they depleted the resources in any given area. The rise of the village could only have happened coincident with another technology: farming.

Çatalhöyük was built overlooking the Konya Plain, on a twenty meter high mound. The plain itself was rich alluvial clay soil, perfect for the growing of primitive wheats and barley which would go into the baking of bread and the making of a kind of a beer. They also grew flax, lentils, chickpeas, and, of course, grapes. Animals came shortly after; likely wild boars became pigs through hundreds of generations of somewhat accidental selective breeding; the rowdier ones would be eaten first, favouring the docile ones. Similarly, goats came from the Ibex. All domesticated cattle can be traced back to a single herd of wild aurochs. And so on.

Now, interestingly, Çatalhöyük is not near the Mediterranean Ocean, being some 120 km inland. It is also one thousand meters above sea level, so it would have been around six degrees cooler than the coast, an important consideration in the Mediterranean. But even though the village was one kilometer above high tide, the neolithic builders built it an additional twenty meters above the plain it rests on, on a man-made mound. They were unusually concerned about flooding, it would seem. And that's odd, if you think about it, because a few generations previously these people would have been nomadic hunter-gatherers, or, more likely, fisher-gatherers; they would have lived on the Mediterranean with its never ending supply of sea food.

Just like the people of Tel Hreiz in Canaan, which would one day be called Israel. They had a thriving village of well over a hundred people. Archeological evidence suggests the people of Tel Hreiz, and at least fifteen other villages up and down the coast from them, were engaged in fishing, agriculture, and even the making of olive oil. They lived right on the coast, perhaps seven or ten feet above high tide. But high tide, and even the coastline itself, was a fickle thing in 6,500 BC. So the people of the tel built a huge sea-wall, some 100 meters long, to keep the sea in its place. It didn't work. Tel Hreiz, and all of its neighbouring communities, are currently three to fifteen meters below sea level, between one hundred and one thousand meters out into the ocean from the present shore. And the doom came suddenly: in nearby Atlit-Yam, twelve meters down, there are the remains of stacks of fish ready for processing or trading that will never happen. Speculation is that the end came by way of a tsunami. And that brings us back to North America, and Lake Agassiz.

Lake Agassiz went through many iterations, or phases, in its life, and these different phases saw the release of vast amounts of water into the world's oceans. Maybe that gave the neolithic peoples living around the Mediterranean fair warning to build high up in the mountains, or to construct sea walls. Maybe not. But it is true that in its final phase, the Ojibway phase, Lake Agassiz covered more than 800,000 square kilometers to a depth of as much as a quarter of a kilometer - well over 150,000 cubic kilometers of fresh water. And as the Laurentide Ice Sheet retreated north, there came a day when the plug blocking all that water from flowing into the Atlantic Ocean by way of Hudson's Strait was breached, and a vast wall of water escaped, raising sea levels, some say, by as much as 2.8 meters worldwide. Whether it happened all at once, resulting in a global tsunami, or whether it happened over a much longer period of time, people are still debating. There is evidence of a tsunami from the period near Labrador, but finding evidence of long-ago and very much underwater tsunamis is tedious work. In any event, the breaching of the ice plug released enough fresh water into the Atlantic Ocean that the Gulf Stream was shut down for hundreds of years; that had the effect of lowering the temperature, almost overnight (maybe more like a decade), by eight degrees in the Northern Hemisphere. This bursting of Lake Agassiz, the dramatic rise in sea levels, and the equally dramatic climate change, all occurred around 6,500 BC. Right around the time the village of Tel Hreiz was inundated. And right around the time the farms of Çatalhöyük became unproductive and were abandoned. And, who knows. Maybe right around the time Noah built his ark.

The huge outflow of fresh water from the lake was followed immediately by a huge inflow of salt water from the Atlantic Ocean. The depression that was previously Lake Agassiz and would one day be Hudson's Bay became the Tyrell Sea; roughly twice as large as modern-day Hudson's Bay, with shorelines 100 to 250 km further inland than at present. The new sea was quite a bit further south than its neighbouring oceans, and drained a vast region: there were a lot of really big rivers. So it was rich in marine saltwater and freshwater life. The abundant food was quickly discovered by the wildlife. And the wildlife were quickly discovered by the people.

The plains people to the west had been hunting mastodons, but then the ice disappeared and so did the mastodons. So they started hunting buffalo. But then the Mid-Holocene Warm Period happened, raising temperatures by two degrees celsius, and that on top of the eight degree rebound when the Gulf Stream started back up. There was wide-spread drought and starvation on the prairies. Compressing a lot of history, involving the ebb and flow of ice, treelines, temperatures, shorelines and people, eventually the ancestors of the Dene people arrived on the shores of the Tyrrell Sea and found a utopia of things to eat.

Now fast-forward to today. The little town of Churchill, Manitoba, sits a little over 120 km offshore in, and 165 meters under the waves of, the Tyrrell Sea. That puts it right on the shoreline of present-day Hudson's Bay where the Churchill River flows into the Churchill Estuary. The estuary has a much lower salinity than does Hudson's Bay, which in turn has a much lower salinity than the Atlantic Ocean. There are annually 700 cubic kilometers of fresh water flowing into Hudson's Bay. The bay is very long and very wide, but not really very deep, averaging about 100 meters. Kind of a submerged prairie. And it has a low exchange rate with its neighbouring oceans. So while a "proper" salinity for salt water is around 31 parts per million, that of Hudson's Bay is in fact 31 at depth, but gradually becoming as little as 2 at the surface, and there is a current of essentially fresh water flowing counter-clockwise around the edges where all of the rivers and estuaries are, especially on the western shore.

These zones of salty and relatively fresh water make for a unique situation in Hudson's Bay: it has both freshwater and saltwater plankton. Plankton are all of the miniscule plants and critters that fish eat and they are the basis of the food chain. And Hudson's Bay has a very diverse chain. Especially in-shore, where the lower salinity and temperature makes for a high biomass.

Apart from supporting a wider range of critters, fresh water also differs from salty in that it freezes faster. That means, amongst other things, that the ice forms sooner around the edges of Hudson's Bay, and in particular the western edges around Churchill, in the fall; conversely, while the pack ice out in Hudson's Bay is still going strong well into the summer, shore ice disappears by April or June in Churchill with the somewhat warmer circulation of fresh water along the coast. Large areas of ice-free water can be pretty appealing if you are a phytoplankton; but they are literally life and death if you happen to be a whale.

April or June is when the beluga whales are mating. Gestation for a beluga is 14 months, so it's actually the previous year's mating that sends expectant moms to the Churchill River Estuary in early July to give birth in a natural crèche free from ice and large marine predators (sharks and killer whales don't like fresh water) and rich in capelin and lake cisco (who do). There are as many as 4,000 beluga whales in Churchill's estuary at birthing time.

April is also mating season for ringed seals. They can actually delay their gestation for 81 days, which then lasts nine months. So a ringed seal is giving birth about a year later in late February or mid-March. Unlike the belugas, they require ice for their births; the mom will dig out a den on the pack ice near her air hole and care for her pup until the pack ice breaks up, usually around late June, early July. Ringed seals enjoy the profusion of marine life to be found around estuaries such as Churchill. And the bears enjoy the profusion of ringed seals.

Polar bears are the largest land carnivore and also technically a marine mammal. When the pack ice breaks up in the summer, the bears who have been living on it swim to shore and largely fast until the fall. Then in October or November, half of them assemble en masse in places such as the Churchill Estuary to await the early arrival of the freshwater ice, which leads shortly thereafter to the pack ice. The other half of the bears are pregnant moms, and they will seek out a den on land and give birth typically to twins before joining the rest of the bears on the pack ice in February or March, right around the time the baby seals are born.

So the unique habitat of Hudson's Bay, and its large estuaries such as Churchill, have led to adaptations by the critters, ranging from plankton, through fish, then on up into whales, seals and bears and ultimately to man, that all mesh and all rely on the yearly cycles of ice. And the ice relies on the weather. But you can't count on the weather.

Tide gauge data has been collected continuously at the mouth of the Churchill River since 1940. And what it shows is that the Hudson's Bay sea level has been dropping by 4.4 mm/year up until 1975 and then 9.4 mm/year after that. It is estimated that, on average, the sea level drops by over a meter every century. Of course, the sea level is actually not dropping at all; it's rising. It's just that the land rise is outpacing it.

Since the glaciers retreated, with all of their weight, the land around the Tyrrell Sea, now Hudson's Bay, has been rising due to a thing smart people call Isostatic Rebound, and I call The Jiggles. If you squish down on a bowl of jello and then let go, it will jiggle back up to where it was before. Or, if you are a giant chunk of ice, and you squish down on the land, and then melt, then the land will jiggle back up to where it wants to be. It is the reason that planets are round. Actually, they're typically oblate spheroids, but that will only cloud today's discussion. So anyway, after 8,000 years of no ice the jiggle is about half way done. If it is a straight-line thing (I have no idea myself) then in another 8,000 years Hudson's Bay will be Hudson's Plain. This will mess with the heights of land, and all of the rivers are going to go elsewhere. As will the seals, whales and bears.

But it's not like everybody has 8,000 years to adapt. You may believe in global warming, or you may not. Either way, it is a fact that the polar bears of Churchill, who only ever eat on pack ice, have lost twelve days of pack ice on either end of the season in the last couple of years. Since they usually eat one seal every 5 days, this is five fewer seals that the average bear will eat in a year. Bears today are twenty pounds lighter and ten percent shorter than they were a few years ago. The mothers, who are only in a position to eat for four months out of the year at the best of times, cannot tolerate the loss of the best part of a month of feeding. Wolves have started catching polar bear cubs, and the weakened mothers cannot prevent it.

But it may not be global warming per se that is going to get the polar bears of Churchill. With the reduction of winter sea ice there has been a corresponding increase in shipping, and we'll talk more about the North West Passage tomorrow. For today, we'll just say that Hudson's Bay's unique geography - a large bay a great deal to the south of its arctic inlets - has shielded it from any number of invasive species who can't tolerate the cold journey it would take to get here. Unless they were to hitch a ride in the ballast water of a grain ship. Large grain shipments started up again in 2019 in the Port of Churchill. That means the bay is accessible to dozens and dozens of barnacles, crabs, mollusks and plankton species that have never before called Hudson's Bay home. And their potential effect is entirely unknown.

So anyway, today we're off to Churchill Manitoba, the Polar Bear Capital of the World. The forecast looks nice. But, then again, you can't count on the weather.

A rainbow. Clear sailing today, I guess.

A rainbow. Clear sailing today, I guess.

|

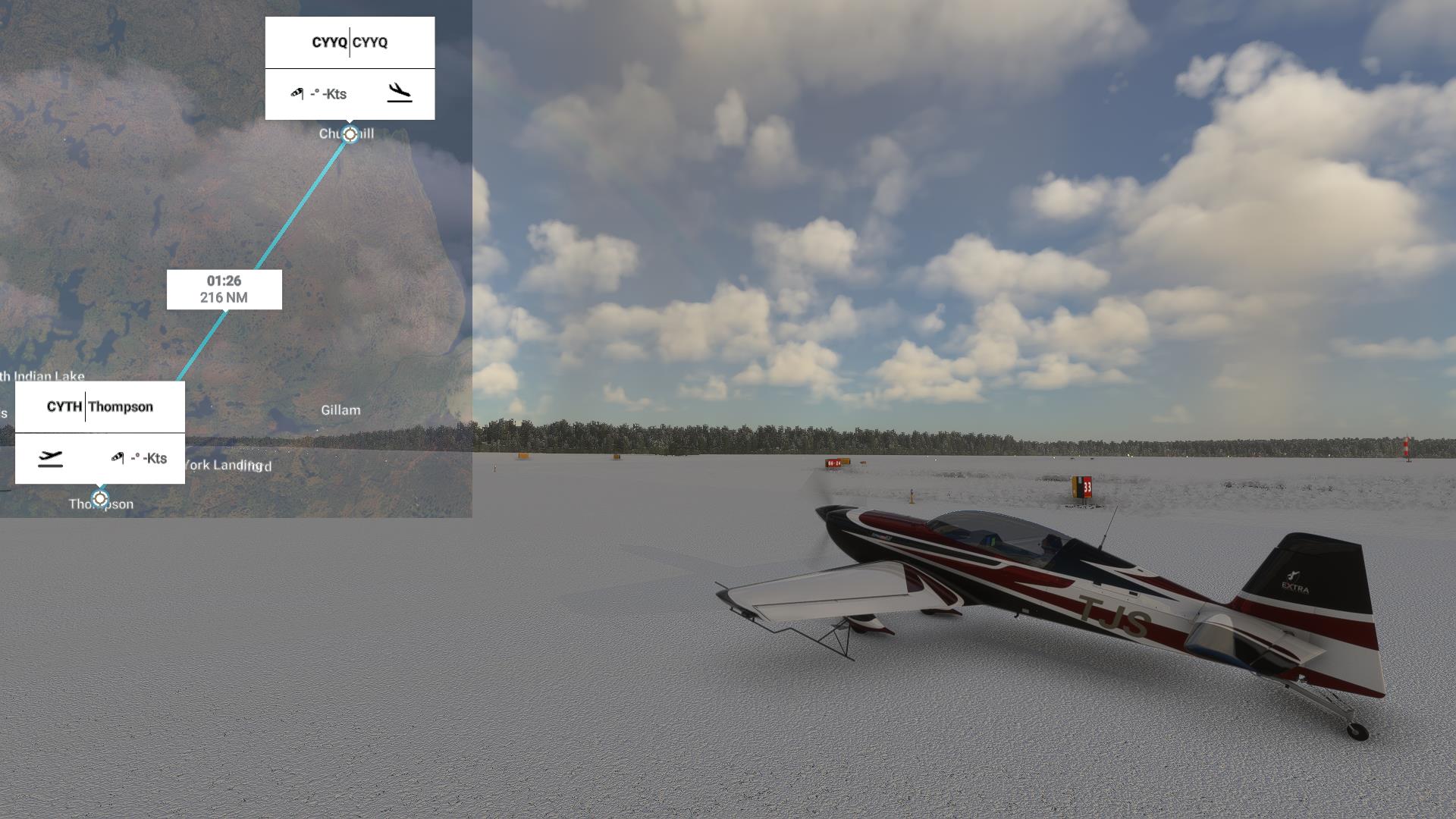

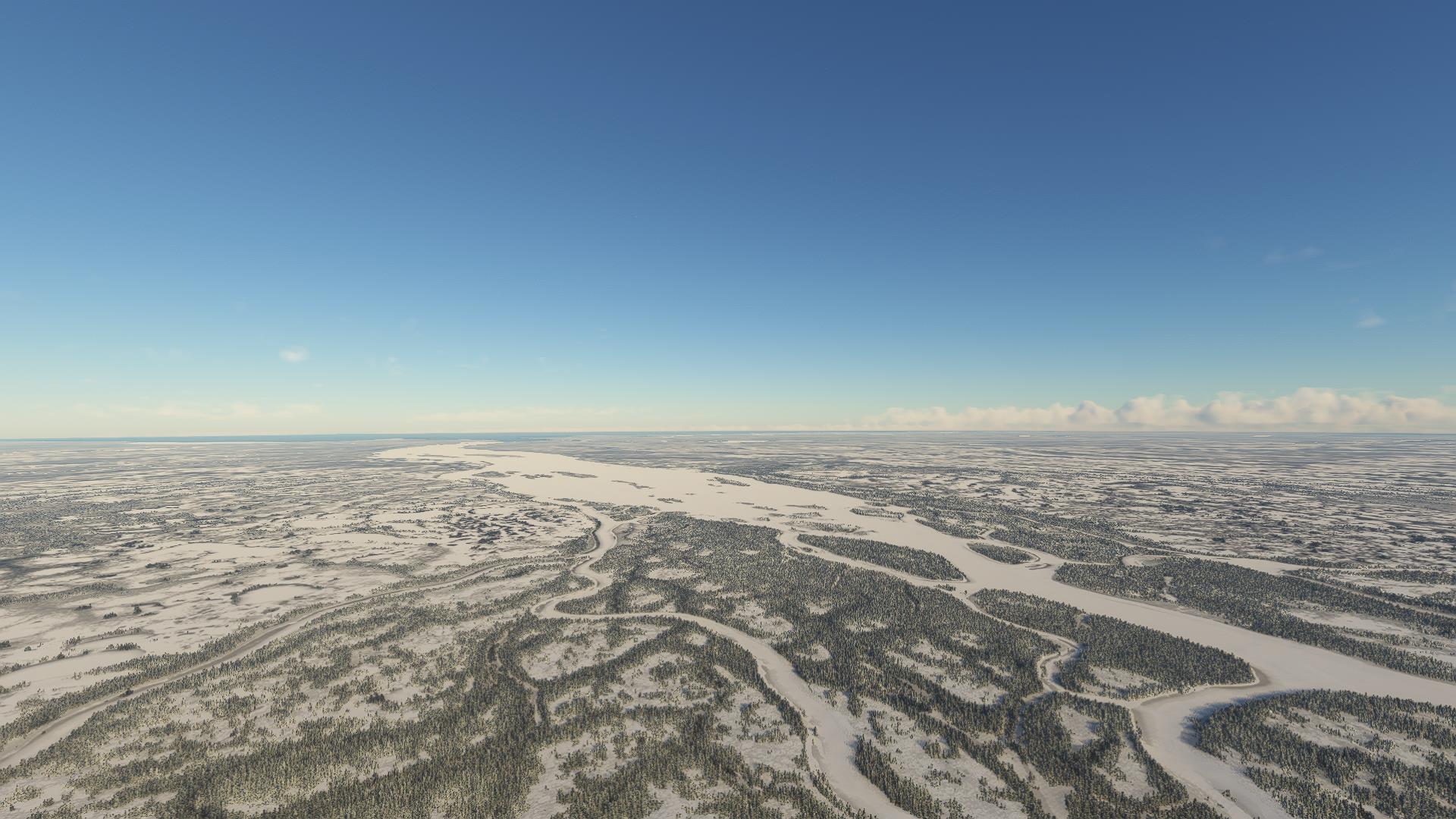

Man, this place is flat. I can really picture the bottom of a huge lake here.

Man, this place is flat. I can really picture the bottom of a huge lake here.

|

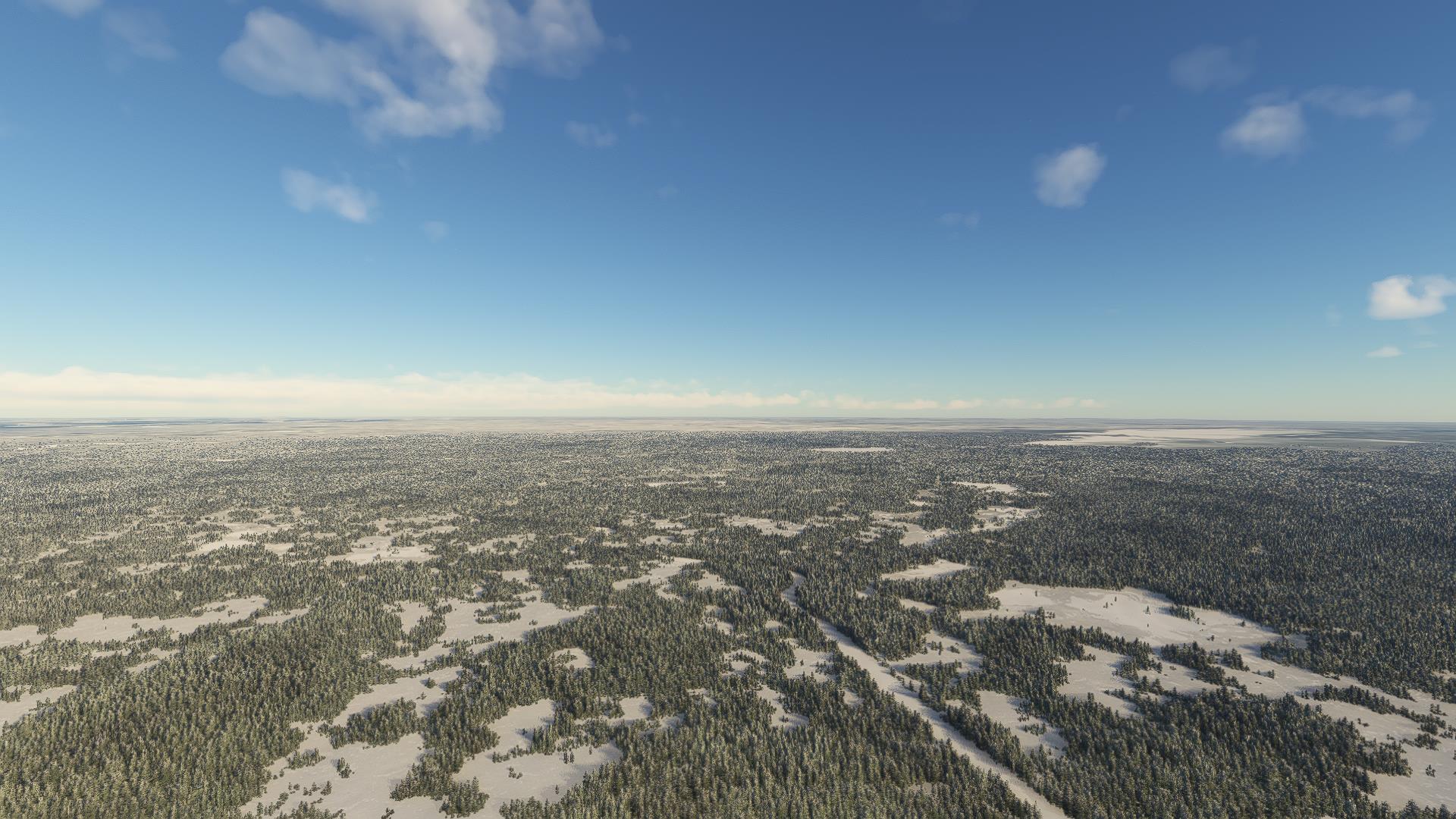

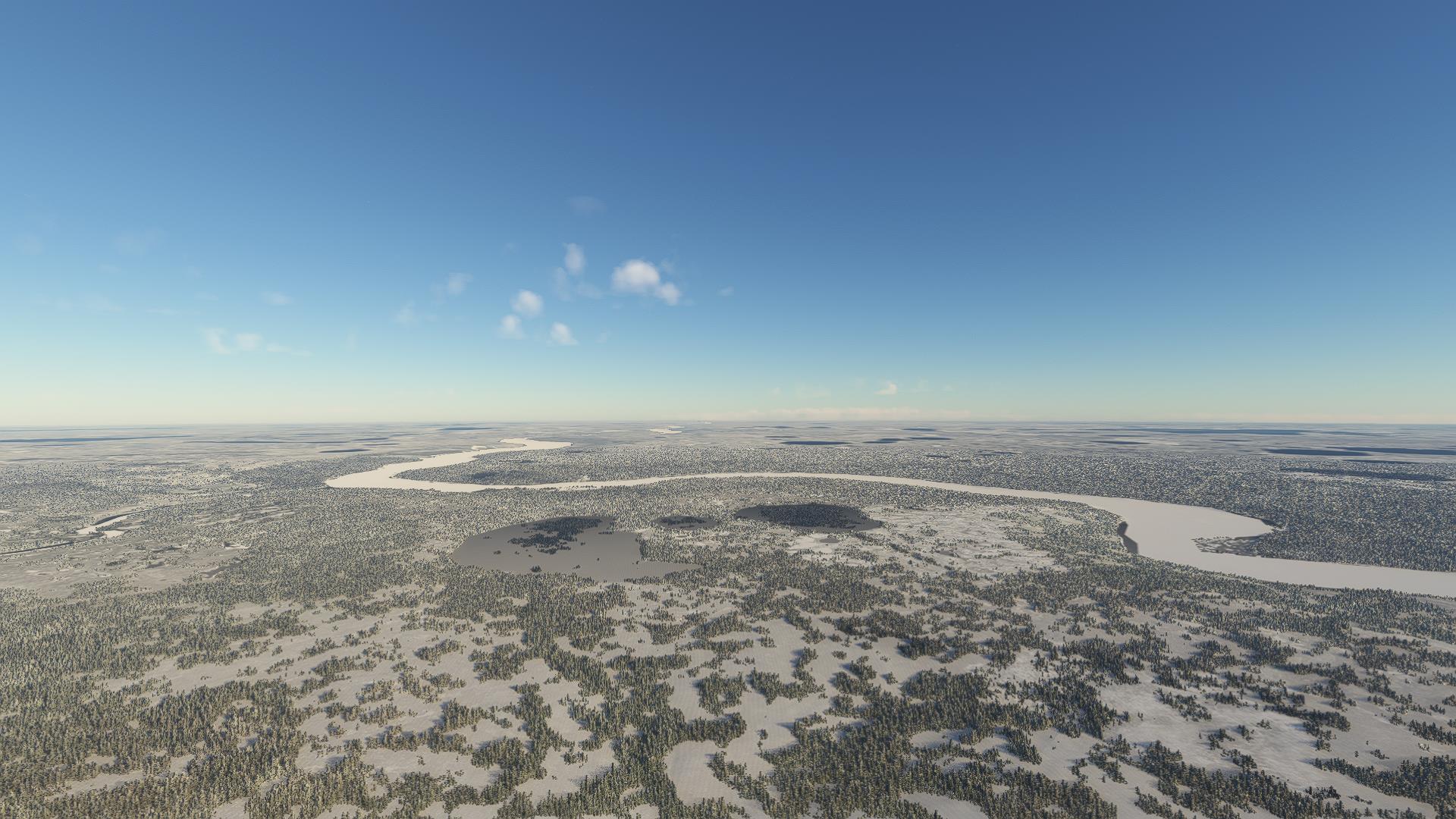

Churchill River. We basically follow that to destination.

|

|

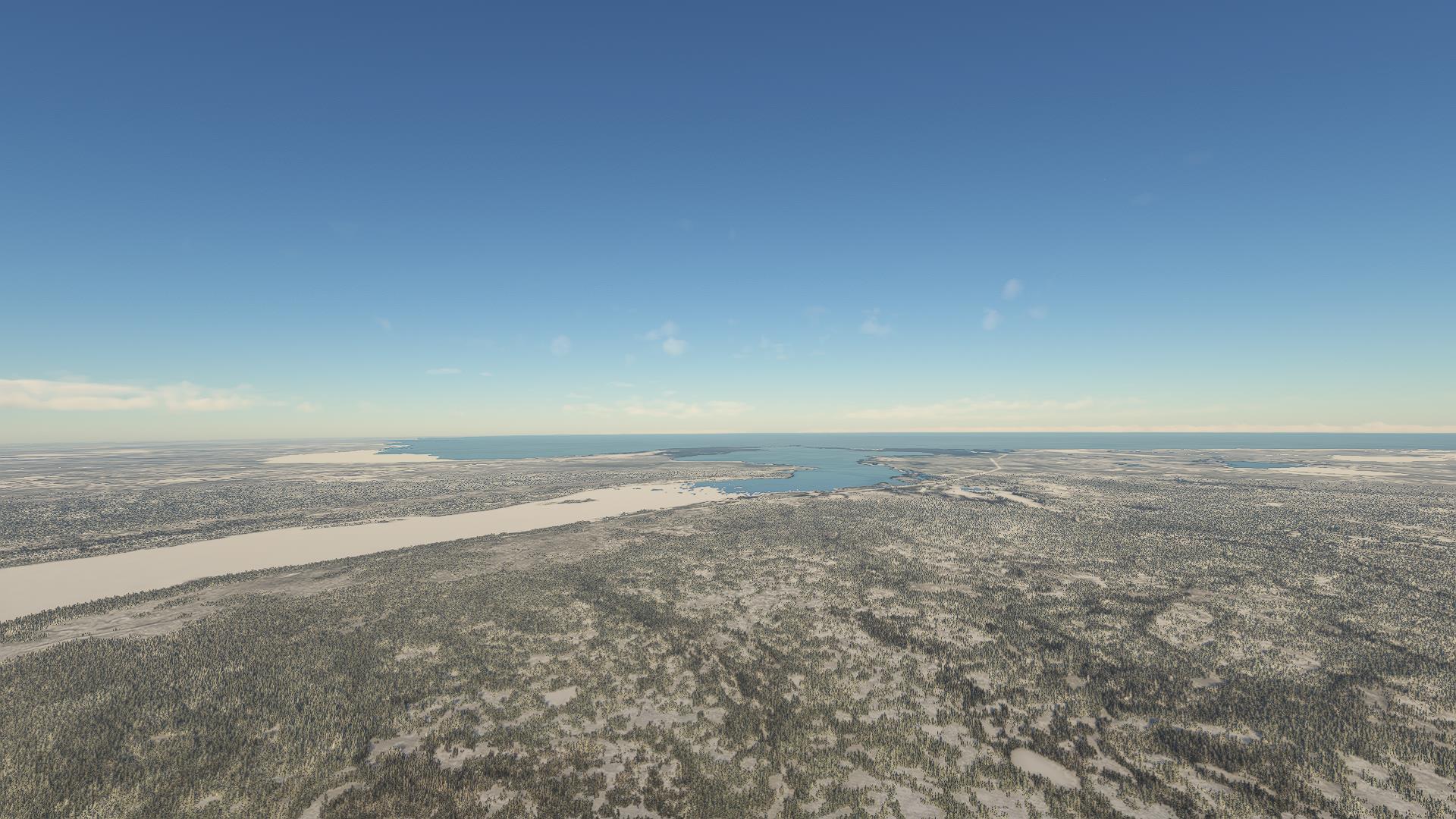

This is the transition between river and estuary.

This is the transition between river and estuary.

|

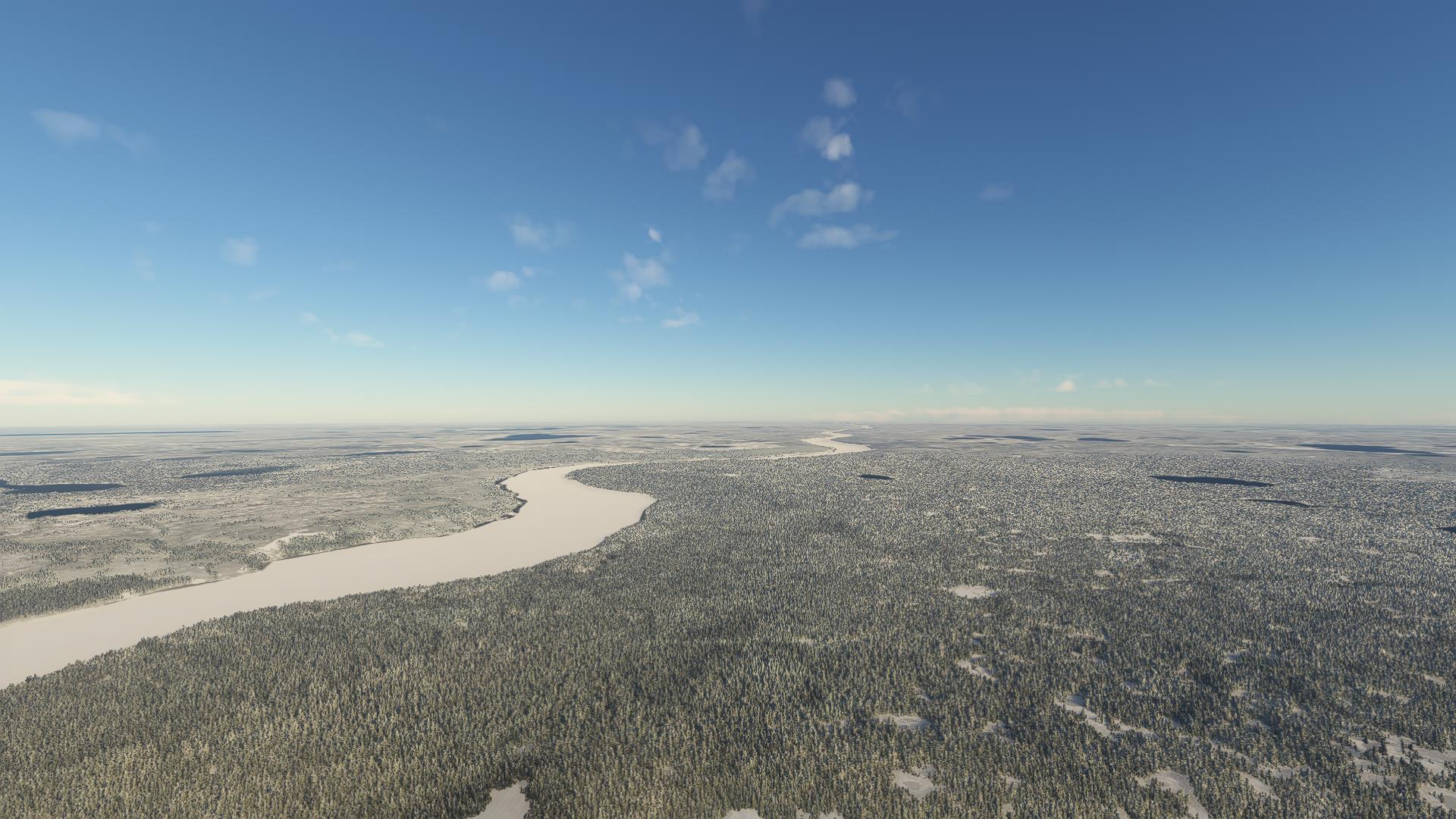

And that's as far as the freshwater ice has made it so far.

And that's as far as the freshwater ice has made it so far.

|

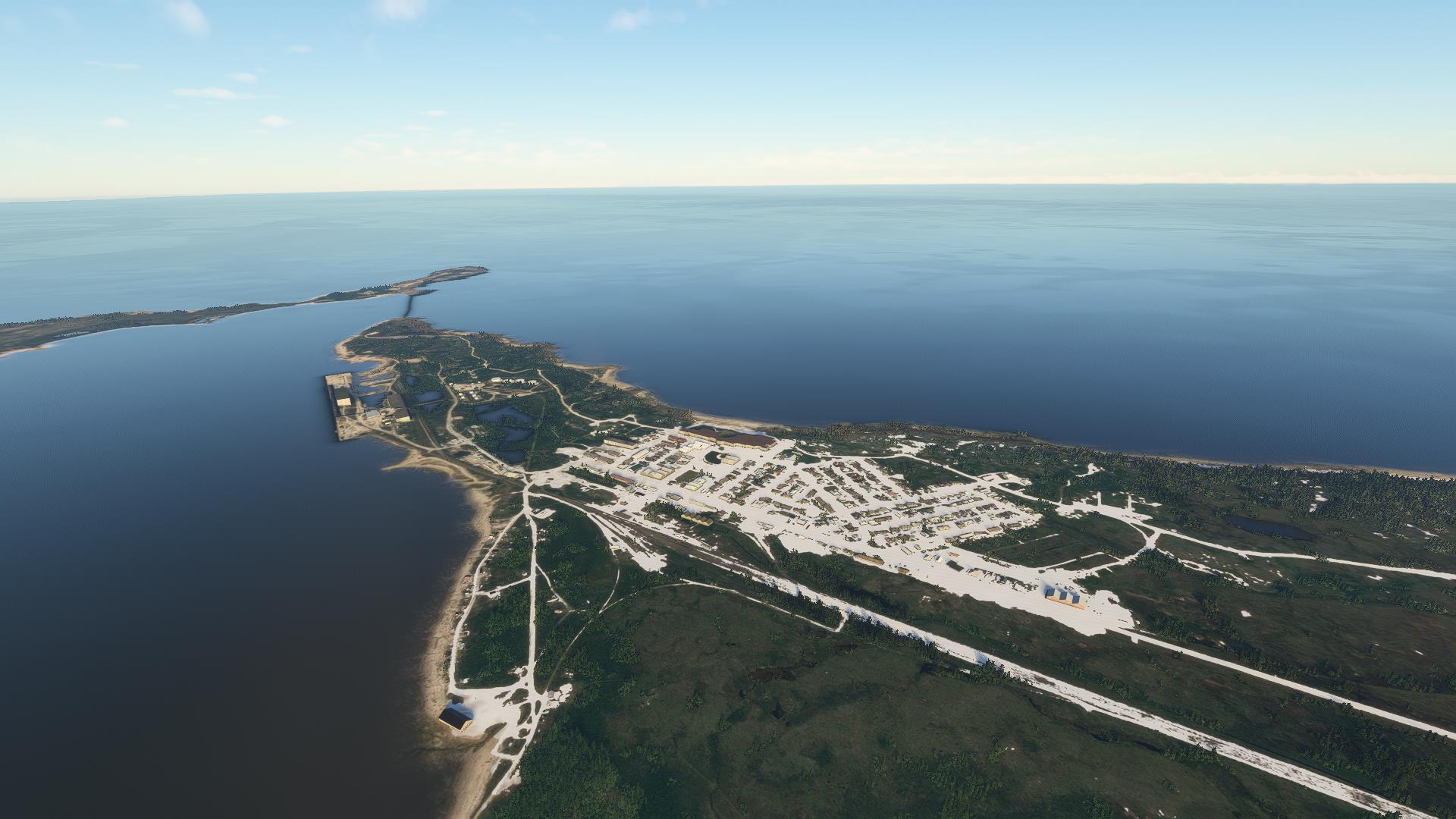

And there's the little town of Churchill. Yes, it is illegal to lock your car here.

And there's the little town of Churchill. Yes, it is illegal to lock your car here.

|

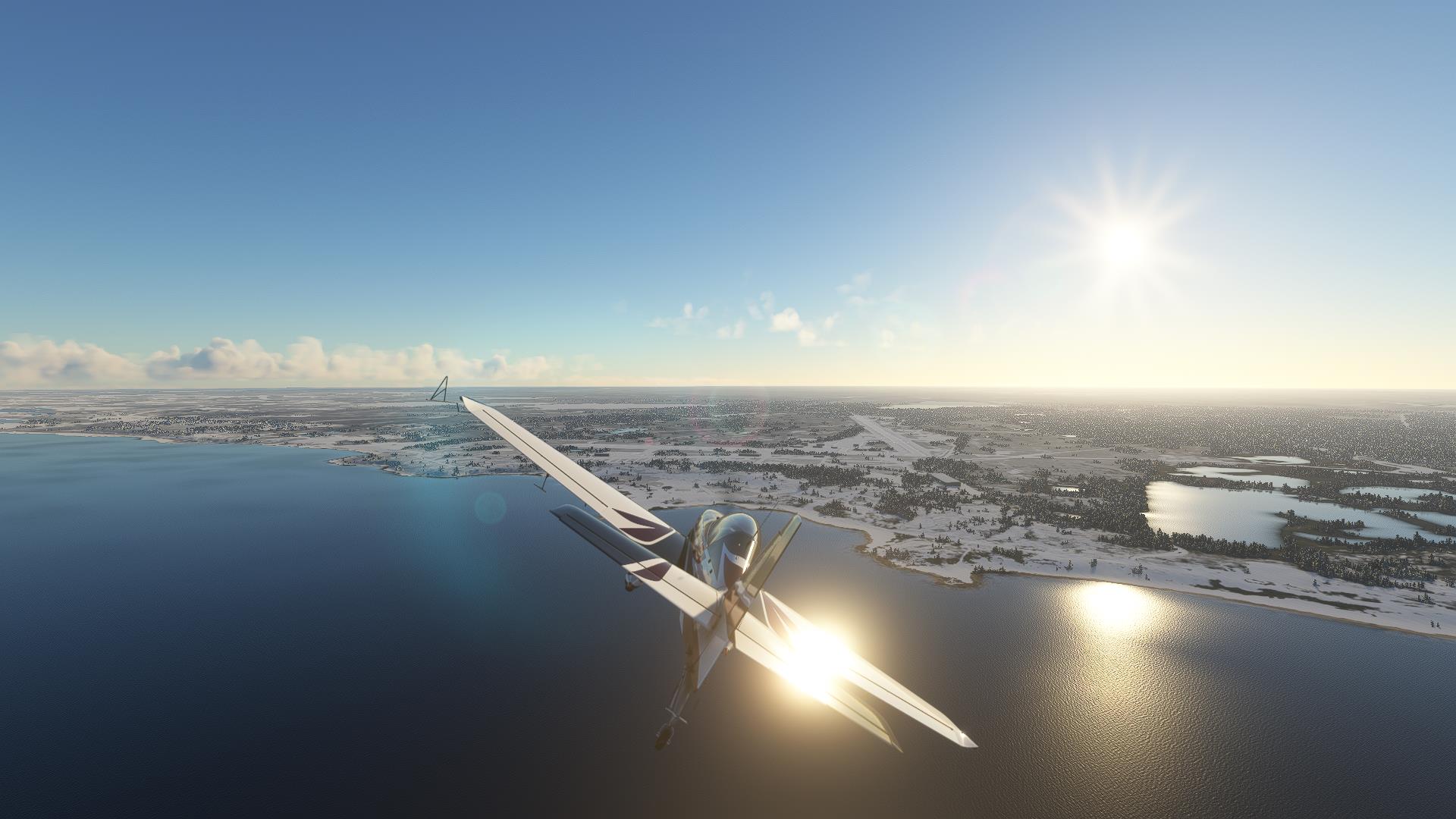

Airport's close by. Really, this place is so flat they can call anything an airport.

Airport's close by. Really, this place is so flat they can call anything an airport.

|

Well, this is it for Manitoba. Tomorrow we're off to the far north.

Well, this is it for Manitoba. Tomorrow we're off to the far north.

|