Midland

'Twas in the moon of winterime...

The name Ontario may derive from the Wendat word Ontarí:io, meaning Great Lake. Or it may derive from a totally different Iroquoian word meaning Beautiful Water. In any event, that is the name of the lake that is a major feature and the namesake of the province of Ontario.

Long before it was a province, the region was settled by members of one of the "Paleo Indian" cultures that arrived after the last glaciation, around 13,000 years ago. They were likely Clovis people, named after a site in Mexico where a certain technology of fluted (chipped) obsidian spear point was first discovered. A Clovis point was discovered in Sarnia in 2015, along with several other artifacts that point to a Clovis nation of perhaps as many as 100 or 200 individuals occupying all of the land mass of Ontario that was not under a sheet of ice at the time. They would have used their Clovis points to hunt caribou and mastodons in an environment more like the subarctic tundra than today's southern Ontario.

Over time, the Clovis nation spread out following the retreating ice sheet. Those heading north and west became the Algonquian peoples; those heading east became the Iroquoian. Algonquian and Iroquoian should not be confused with languages or culture; they may have started out that way but quickly became language families. English is a Germanic language as is German, but the two languages, their original speakers and their cultures are vastly different. In a similar manner, the Algonquians to the north-west were all related historically but were in fact the Ojibwe, Cree and Algonquin people. These people lived in an extreme environment and so they led a nomadic life, ranging the wilds in family units during the winter and gathering in larger groups at sites where the fishing was particularly good for the summer. While they were fiercely protective of their hunting grounds from invaders, such as the Dakota to the west, their harsh environment tended to make them a fairly peaceable people.

The Iroquoians, on the other hand, practised warfare as a way of life. The Iroquoian people had a much easier climate than the Algonquians, and so they could build permanent structures and even grow crops. The structures they built were generally fortified - not against nature but against people. Long running feuds would develop between groups, and a raid from the one to the other that resulted in casualties would trigger a revenge raid to take captives to replace those lost, which would trigger another revenge raid, and so on.

In the south-east of what would become Ontario were to be found the Tionontati, Attignawantan and Wenrohronan, who would collectively form the Wendat confederacy and be referred to as the Hurons by the French, after the Old French Hure, or Ruffian. To their west were the Aondironon, Wenrehronon and Ongniaahraronon people who would collectively be called "the Neutrals" by the French, as they were a sort of a buffer between the Wendat and the group to the south and east: the Haudenosaunee. These were Iroquois people from the nations of Seneca, Cayuga, Oneida, Onondaga and Mohawk. The Haudenosaunee were traditional enemies of the Wendat; members of the Bear, Deer, Cord and Rock Wendat peoples were driven out of the St. Lawrence valley in antiquity to join up with the peoples already resident in southern Ontario, and stories of this outrage likely lived on around the campfire of a night.

So war was a commonplace in the land that would one day be Southern Ontario. But it was mostly confined to what could be considered border skirmishes. Large scale, all-out war was unheard of until the Europeans arrived. They were looking for furs.

Fur had always been important in European civilization. In pre-coal Europe, that is, before the organization of the coal distribution infrastructure that would fuel the industrial revolution, furs were vital to the common folk simply as a way to keep warm. Central heating at the time involved an open fire in the middle of one's hovel, the smoke simply exiting via the breezy roof. Any animals that were a part of the family were likely to be housed in the same hovel, perhaps separated from the people by a wall but essentially adding a few degrees of warmth to the structure. It was cold, and it was prudent to dress warmly.

Of course, those of gentle birth were less likely to need furs simply to survive. The circulating fireplace with a raised grate had been invented by the 1600s, and for the really wealthy, the hypocaust (a large fire underneath the structure) had been around since the times of the Romans. The fireplace required a masonry chimney, quite the luxury, and the hypocaust required slaves or servants to continually feed it. Still, if you had the money you could afford to stay warm without the need of furs. So for the wealthy, fur linings to their garments became more of a symbol of status.

In the early part of the middle ages, the furs of choice were either minever or gris, fancy names for squirrel. A squirrel lined garment might have set you back four pounds in 1407, or about what a labourer would earn in two years. Or you could get marten for ten pounds. If you were exceedingly well heeled, sable could be had for around thirteen pounds. No matter what your tastes, the furs probably came "from the north", which generally meant Novgorod, what we would today call Russia. For a thousand years this land had been the primary supplier of furs for all of Europe - wolf, fox, marten, beaver, rabbit and of course squirrel pelts were harvested in the Targa and sold through trading posts around the Baltic and Black seas, as well as markets in the low countries such as Holland. When the Tsar invaded Siberia, Russia found itself able to supply Europe with ermine, arctic fox, sable, lynx and sea otter as well. They were making a huge profit on the sale of these furs. And wherever there is profit, there is always someone wanting to take it.

The Hanseatic League was formed largely by a few northern German towns in the late 12th century as a sort of a coop of common commercial and defensive interests. It quickly grew and expanded, and by the 15th century it pretty much had a monopoly on ocean going trade in the North and Baltic seas. Relations were understandably strained between Novgorod, who produced the furs, and the Hanse, whom they had to deal with exclusively to get their furs to market. Relations were also strained between the Hanse and the English, who had to grant special privileges to the Hansards resident in England in order to continue receiving furs. These tensions would occasionally boil over, resulting in years of scarce furs until relations could be patched up. Eventually the Hanseatic League collapsed, but the vacuum left by them was quickly taken over by pirates and the Danish.

At about the same time that the Hansards were losing power, fashions were drifting away from furs per se and gentlemen's hats were becoming the vogue. For various reasons, beaver pelts are the ones you want for a hat, but they must be "felted" first. The felting of beaver pelts was a closely guarded trade secret in Novgorod and they pretty much had a monopoly on it. And then two things happened. Russia ran out of beavers, and the Tartars invaded.

So suddenly, there was a confluence of factors making North American furs a hot commodity. All of Europe was sick of trade monopolies; the fur of choice was in short supply anyway; and suddenly the technology needed to make felt hats was fleeing an invasion and looking for a place to live. And that brings us to the Beaver Wars.

In 1628 the Dutch East India Company was one of the larger European players in the new world. New Netherland was their colony, and it encompassed much of what would later become New England, although Britain was also claiming parts of this territory at the same time and setting up colonies in such places as Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth.

France's Compagnie des Cent Associes was another major player in North America; they claimed pretty much everything else in Northern North America (Spain's territories were to the south) that the Dutch did not as far west as the prairies. The land that drained into Hudson's Bay was claimed by the French but also by England and that claim would one day lead to the Hudson's Bay Company. So broadly speaking, the land that would become Southern Ontario was occupied by Neutrals, Wendat, other Iroquoian groups and the French, but surrounded by Algonquians (also partnered with the French) to the north and east and the Haudenasaunee and Dutch to the south of the great lake and the river flowing out of it.

The Dutch had been supplying their First Nations hosts for years with tools, blankets and weapons, for which they received animal pelts. Their hosts were originally the Mohican people, but when the Mohawks invaded and pushed the Mohicans out of the territory, the Dutch simply carried on with their new hosts. Business was good; so good, in fact, that the region around the Hudson River ran out of beavers by 1640. So the Mohawks began looking north.

Meanwhile, all of the Algonquians and the Iroquoians indigenous to the lands above the lake and the great river were allied to and trading with the French. But the French would not supply weapons to heathens, deeming them untrustworthy. A warrior would have to first convert to Christianity, and then they could get an arquebus (the forerunner to the musket) as a gift. So the Mohawks, allied with the Oneida, were meeting determined, but fruitless opposition when they started invading the Algonquins of the Ottawa Valley and the various Algonquian peoples of the St. Lawrence valley.

The French were not purely driven by business interests as were the Dutch. So to some degree they cared about who was in power - especially if those in power were Christians. Also, the Haudenosaunee were being egged on maybe just a little by the Dutch to harry the competition. So the Haudenosaunee, and in particular the Mohawks, found themselves directly in conflict with the French as well as those whose land they were taking. There were Haudenosaunee attacks on Montréal and as far east as Tadoussac, countered by French invasions of Iroquois land, burning of crops, kidnapping of chiefs, that sort of thing. By 1645 things were quite out of hand, so the French called the Iroquois leaders to a conference in New France to sort things out. They agreed to almost all of the Haudenosaunee demands. But the next year, when 80 canoes full of Haudenosaunee goods arrived in New France, they were told to sell them to the Hurons, who would then sell them to the French. Of course, the Hurons did not have what the Haudenosaunee were after, which were tools, blankets and weapons. So the war was back on, with the Hurons, more properly called the Wendat, in the cross hairs. Which brings us to Sainte-Marie-au-pays-des-Hurons.

St. Marie among the Hurons was the first European settlement in the land that would one day become Ontario, but was at that time Wendake, the land of the Wendat people, within Turtle Island, the whole of North America. It was founded in November of 1639 by 18 Europeans in total, two of whom were the Jesuit Fathers Jérôme Lalemant and Jean de Brébeuf. They used their fortified settlement as a base of operations to preach the good news to local Hurons, and to show them the superiority of the European way of life. Jean, in particular, was fond of adapting Christian Theology to the existing Wendat beliefs so as to make them more palatable. He was also something of a song writer, and penned 'Jesous Ahatonhia', describing how Jesus was coming in order to save everyone from the "spirit who had us prisoner". The song was quite popular amongst the very few Christian converts especially around Christmas time, and, according to Father François-Joseph le Mercier, was the song a fourteen year old Wendat girl sang as she lay dying, probably from smallpox.

Approximately half of the original 25,000 Wendat died from diseases introduced by the missionaries and le Mercier continued his memoirs with how the "Huron Mission has been especially rich, these last two years, in illustrious deaths". Meaning, I suppose, that converts became especially so as their time drew near. In any event, Wendat were dying en masse from European diseases. But the foreign Shamans were not, and this added to their legitimacy for some and to their evil for others. So between the divisions created between the converted Christians and the traditional Wendat, the rampaging diseases and the fact that only a select few were offered firearms, the Wendat were in no position to fend off the southern Iroquois when they started invading. The Wendat in Wendake totally disappeared, the remnants fleeing to New France, in a little less than ten years.

When it became clear that their Huron protectors were being wiped out, those still in the settlement of St. Marie decided to burn it to the ground intentionally rather than have it fall to the invaders. They had already lost eight Jesuit missionaries, martyrs to the cause, who all would later be beatified and then canonized into sainthood. Father Jean de Brébeuf was one of these martyrs. Martyrdom for missionaries, the evil foreign shamans, involved such things as being flayed alive while bound to a cross and receiving a baptism of boiling water. But some of the missionaries had taken a vow that they would accept martyrdom if it were "offered" and they met their deaths with, if not joy, at least a calm acceptance. It is reported that Brébeuf in particular was so quiet and accepting during his death that his tormentors did him the honour of drinking his blood and eating his heart. None of the mocking symbolism accompanying de Brebeuf's death was accidental, nor would it have been lost on the remaining Jesuits.

As for the song that was written by Saint Jean de Brébeuf, it has continued on in Wendake, now a small town north of Québec City, and home of the remaining Canadian Wendat people. Every Christmas, Jesous Ahatonnia is sung in Wendat by the faithful of Notre-Dame-de-Lorette. But an English version of the song has a much wider audience. In 1926, Jesse Edgar Middleton penned the English lyrics to Brébeuf's song, based very loosely on the original, selected Wendat teachings and some early twentieth century imagery of both the nativity and First Nation's culture. This version has been covered by such disparate artists as Burl Ives and The Crash Test Dummies.

So that, then, is the story behind the Huron Carol. Nowadays, the area around Sainte-Marie-au-pays-des-Hurons is a little town called Midland, Ontario. In it you can visit the Martyr's Shrine and learn all about the eight Canadian Martyrs from a Catholic perspective. Across the road is a recreation of the mission on its original site, and just next door is the Wye Marsh wetland. Together these three attractions are a great place to take the kids.

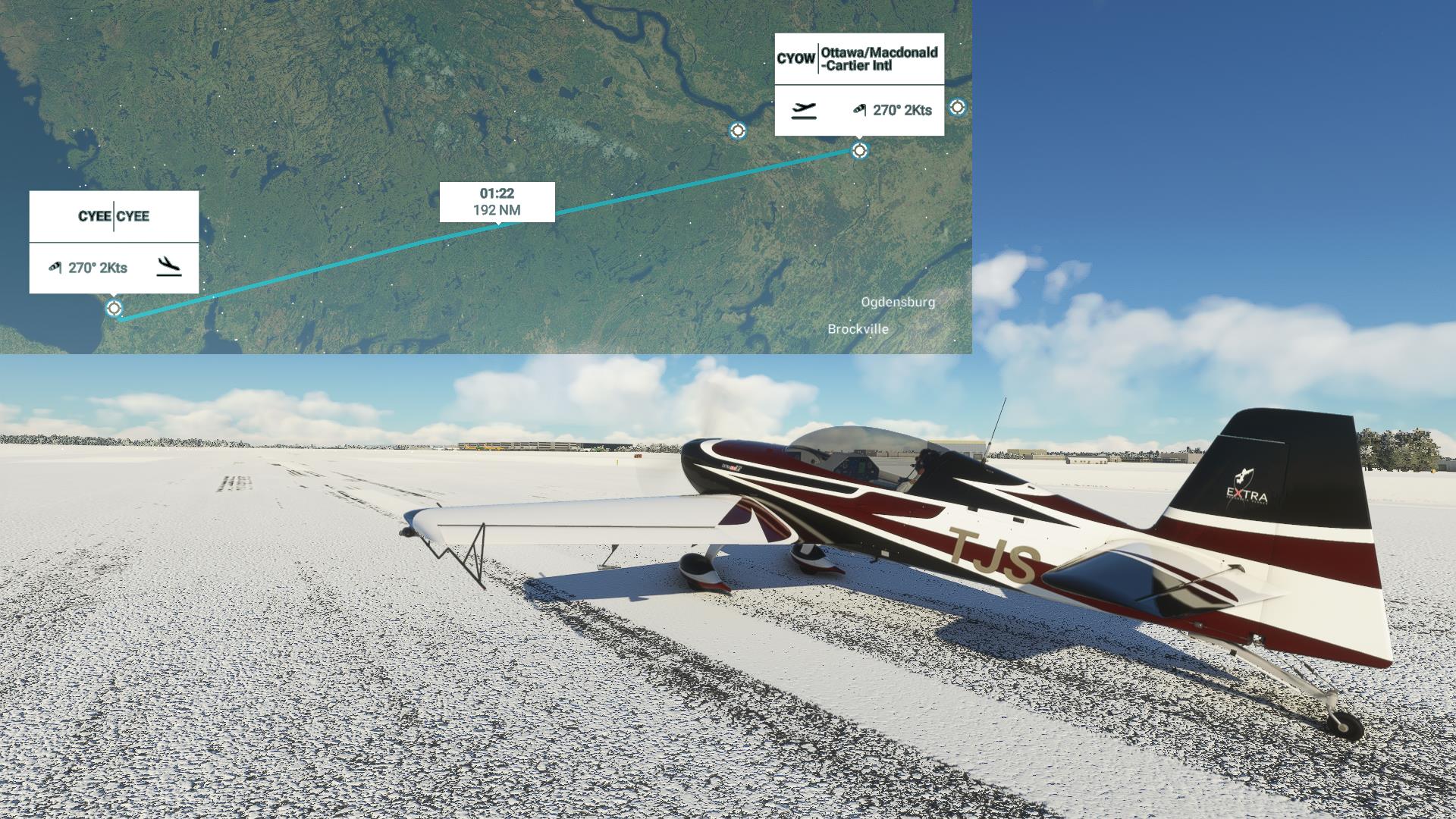

Another lovely day.

Another lovely day.

|

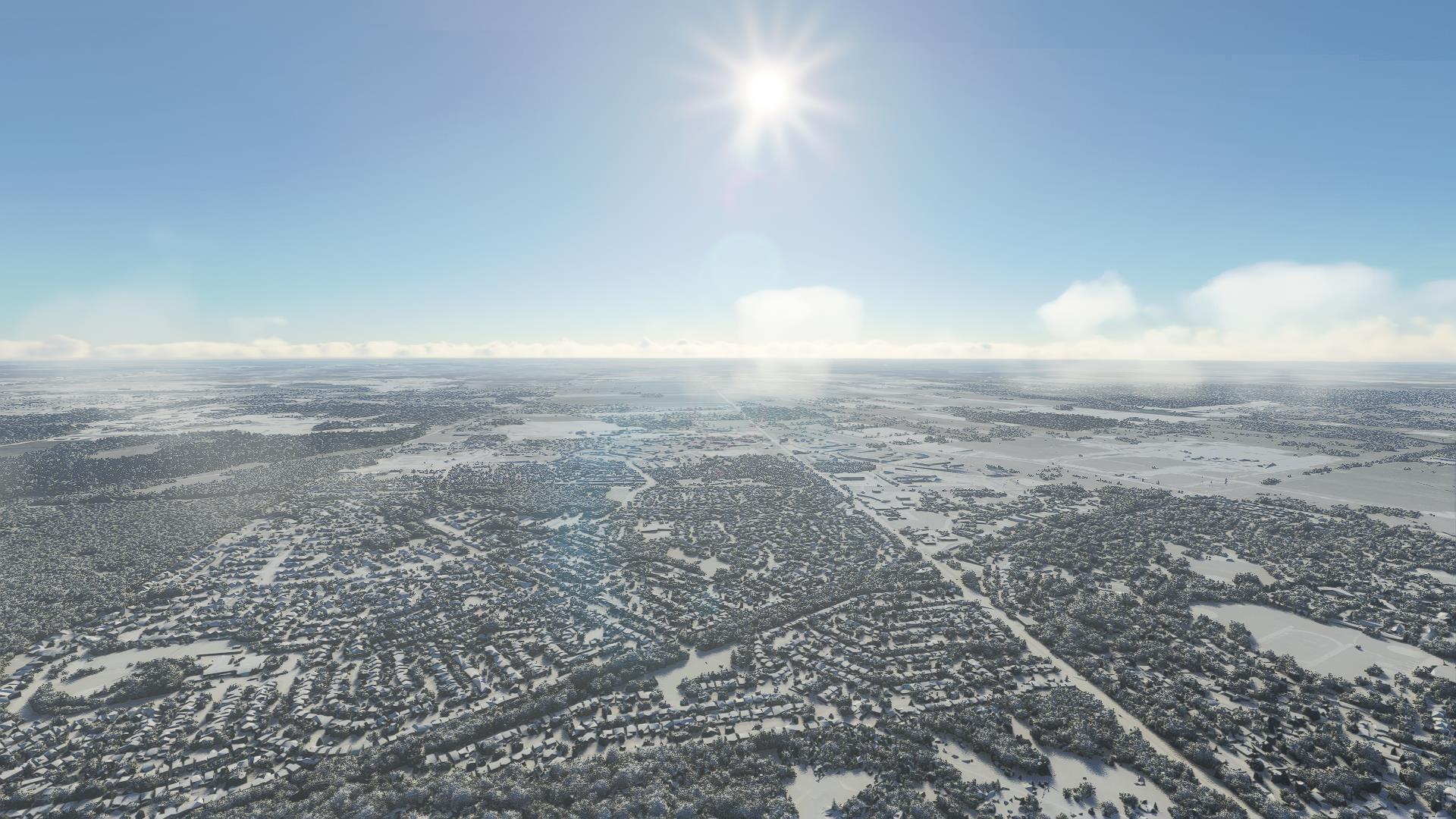

Kanata. High tech and hockey.

Kanata. High tech and hockey.

|

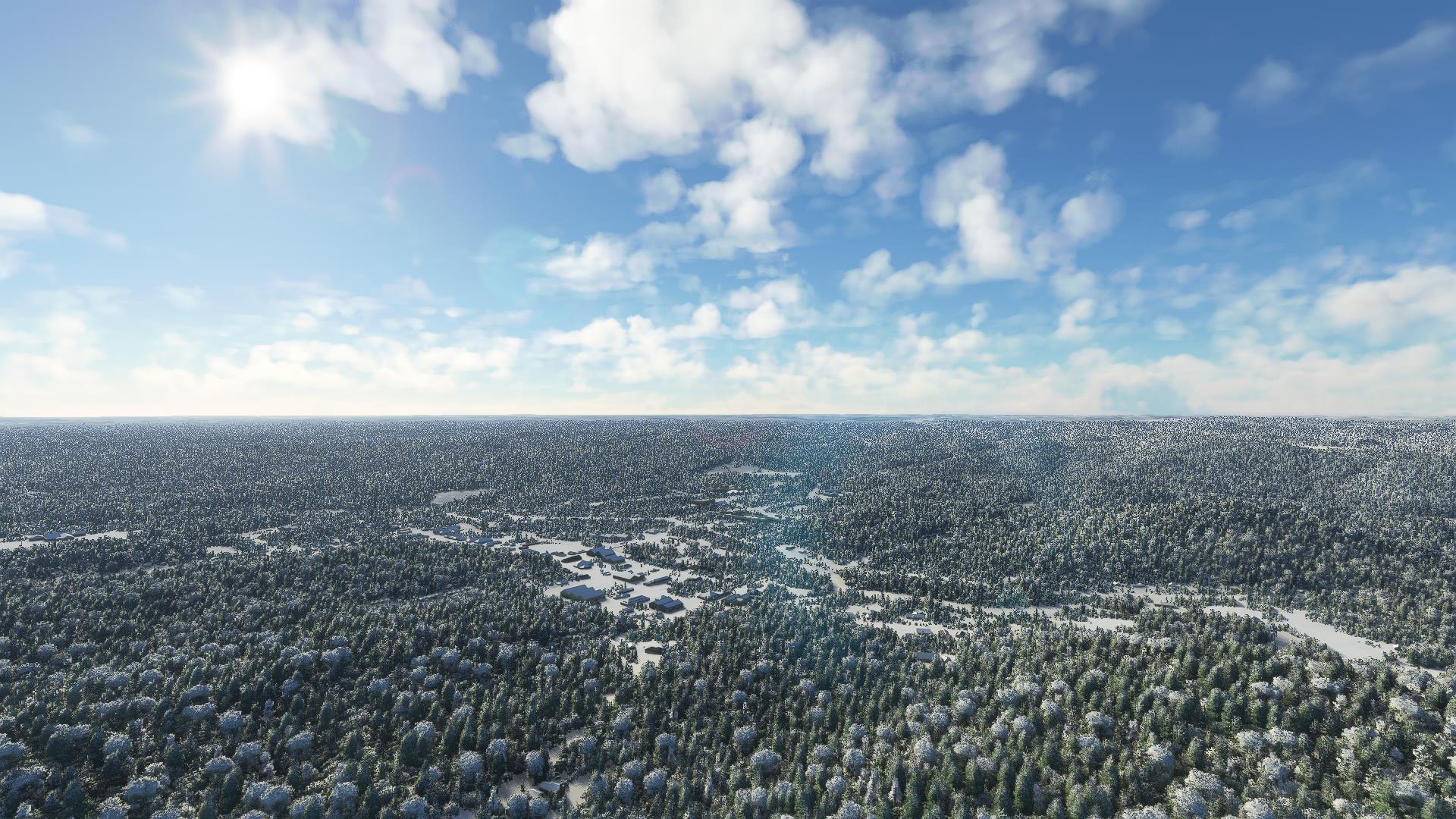

But today's flight is mostly bush. This is part of the Lower Madawaska canoe route into the interior of what is today Algonquin Park. Not for novices; it's white water and wilderness.

But today's flight is mostly bush. This is part of the Lower Madawaska canoe route into the interior of what is today Algonquin Park. Not for novices; it's white water and wilderness.

|

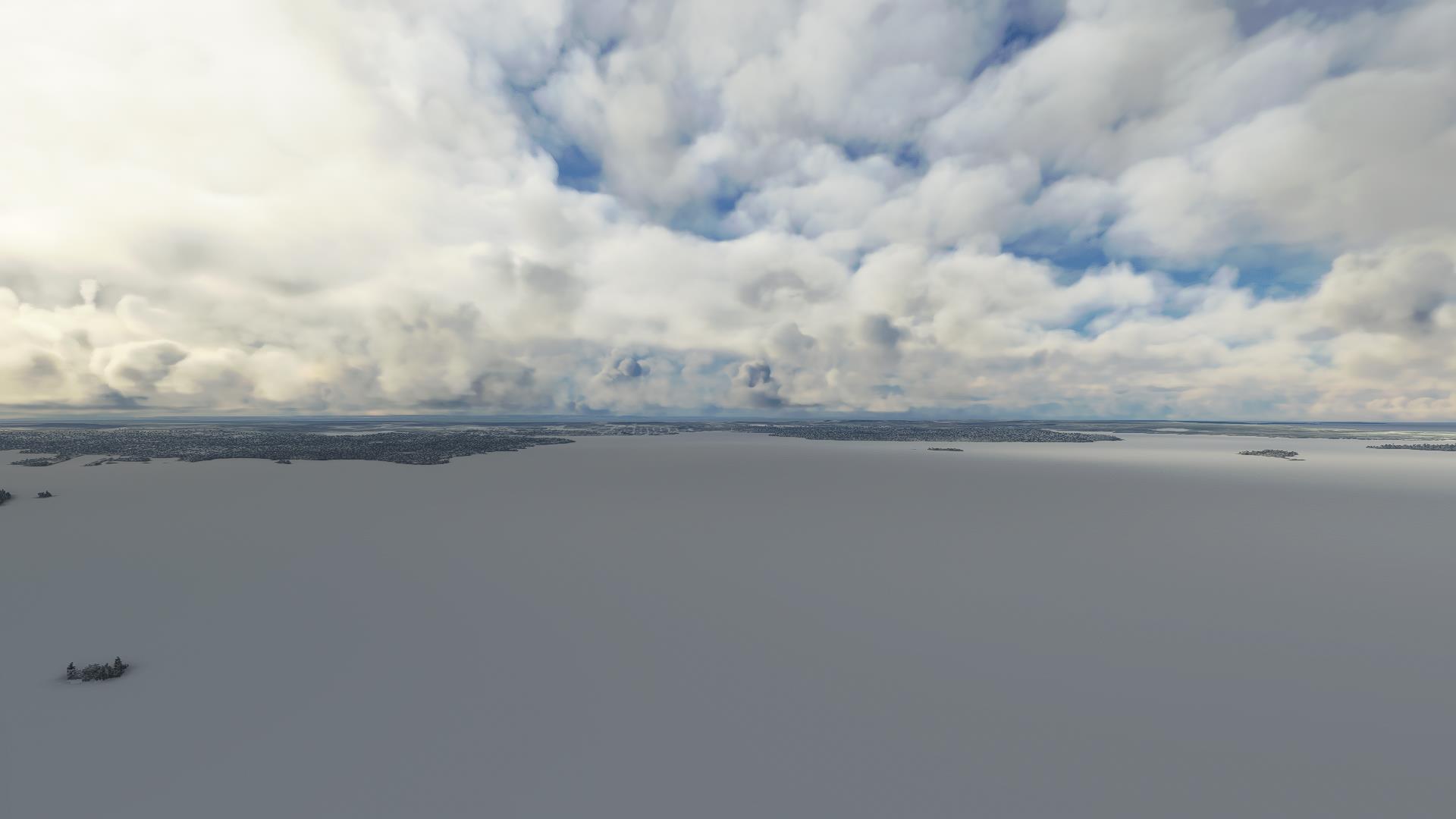

Bancroft. If you're driving through here you want to gas up and maybe get a coffee.

Bancroft. If you're driving through here you want to gas up and maybe get a coffee.

|

And just over there is Midland.

And just over there is Midland.

|

Martyr's Shrine in the foreground, but the historical location of Ste. Marie is that swamp in the background.

Martyr's Shrine in the foreground, but the historical location of Ste. Marie is that swamp in the background.

|

And this is Midland, a very pretty town with a great waterfront walk if you're into such things.

And this is Midland, a very pretty town with a great waterfront walk if you're into such things.

|

So that's about it for today; tomorrow we're going to get cosmic.

So that's about it for today; tomorrow we're going to get cosmic.

|