Weipa

Queensland

Aluminum is the most common metal on Earth and accounts for 8 percent of the Earth's crust. But you'll never find it on its own in nature. That is because it is one of the most reactive metals there are. So much so that if you mix 80,000 kilograms of powdered aluminum with 350,000 kilograms of ammonium perchlorate, throw in 60,000 kilograms of polybutadiene acrylonitrile and add a dash of epoxy you get enough solid fuel to boost a space shuttle into orbit. Now your average Boeing 737 Max 8 weighs 66,000 kilograms, and 80% of it is aluminum. So if your Max 8 decided to spontaneously combust it would get you where you were going really, really fast.

The reason aluminum doesn't go around spontaneously combusting is, ironically, because it already has. At the molecular level, as soon as aluminum is exposed to oxygen it immediately "rusts", giving off vast amounts of heat. At the molecular level. Aluminum "rust", or oxide, is a white powder that sticks to the rest of the aluminum very tightly and it is quite non-reactive. So the metal's very reactivity makes it behave as if it were, in fact, non-reactive. And that is why it is used in airplanes. And any other application where a lightweight, seemingly non-reactive metal is called for.

But since it doesn't occur naturally, and has to be made, it was very, very expensive when it was first discovered. In fact it was twice as valuable as gold. Making aluminum involved heating ore along with pure sodium or potassium in a vacuum, and no step in this process was easy back then. Napolean had aluminum dinner plates and utensils, but they were only for his most honoured guests. The vast wealth available to whomever could produce aluminum more cheaply led to several breakthroughs, resulting in the Bayer process of producing alumina in 1888, and two years earlier, the Hall-Héroult process of electrolyzing more or less pure aluminum from alumina. These two processes are still how you make aluminum today. Ironically, the development of these processes made the price of aluminum fall by 97%.

So in nature, you never get actual aluminum. You can get aluminum oxide - it is a mineral called corundum, and it can turn into saphires and rubies the same way a lump of coal can become a diamond. But mostly what you get is the aluminum hydroxides - gibbsite, boehmite and diaspore - mixed in with the iron oxides goethite and haematite, and other stuff you're likely to find in rocks. This mixture, called bauxite, can be found in various places around the world and comes in two main varieties. If it occurs over carbonate rocks such as limestone or dolomite then it is called carbonate bauxite. This is what you would find in Europe and Jamaica. If the bauxite occurs in conjunction with more silicate rocks such as quartz sandstone, then you get lateritic bauxite. This is what you find on the northern tip of Australia.

Lateritic bauxite is found generally in tropical areas subject to monsoons over the course of millions of years. That is because the relatively thin layers of bauxite material are mixed in with larger layers of non-useful minerals like clay and sandstone. If that was it then it wouldn't be cost effective trying to harvest it. But rain, over time, weathers away the silicate material and concentrates the bauxite. The bauxite of northern Queensland has been concentrating since before tyrannosaurs were a thing.

On the Weipa Peninsula, if you were to start digging, you would find about a half a meter of topsoil. Further digging would reveal the "redsoil", between zero and five meters of it. This is bauxite that has been moved about by water and is found in channels. As you dig deeper, you'll find the regular bauxite layer, between three and twenty meters of it. Any further digging and you'll find yourself at the bedrock. Interestingly, some of the bedrock around here comes from Canada. 1.7 billion years ago Canada and Australia were joined at Western Laurentia. But I digress.

After you harvest your bauxite using "environmentally responsible strip mining methods" (you can't make this stuff up) then you subject it to the previously mentioned Bayer process. You crush it, wash it, dry it, and then dissolve it in caustic soda. After filtering to remove the "red mud" you pump it into tall tanks called precipitators. To these tanks are added aluminum hydroxide "seeds" which grow and settle to the bottom of the tank. These are then removed, washed, and heated (a great deal) until they turn into aluminum oxide, a fine white powder that makes a great abrasive. Or you can add it to paint to make it sparkle. Or you can use it to convert hydrogen sulfide into sulphur, which smells slightly better. Or you can subject it to the Hall-Héroult process: dissolve it in molten cryolite (sort-of salt), stick in a couple of electrodes, zap it, and you end up with mostly pure aluminum and a vast amount of tetraflouromethane and hexaflouroethane, both greenhouse gasses.

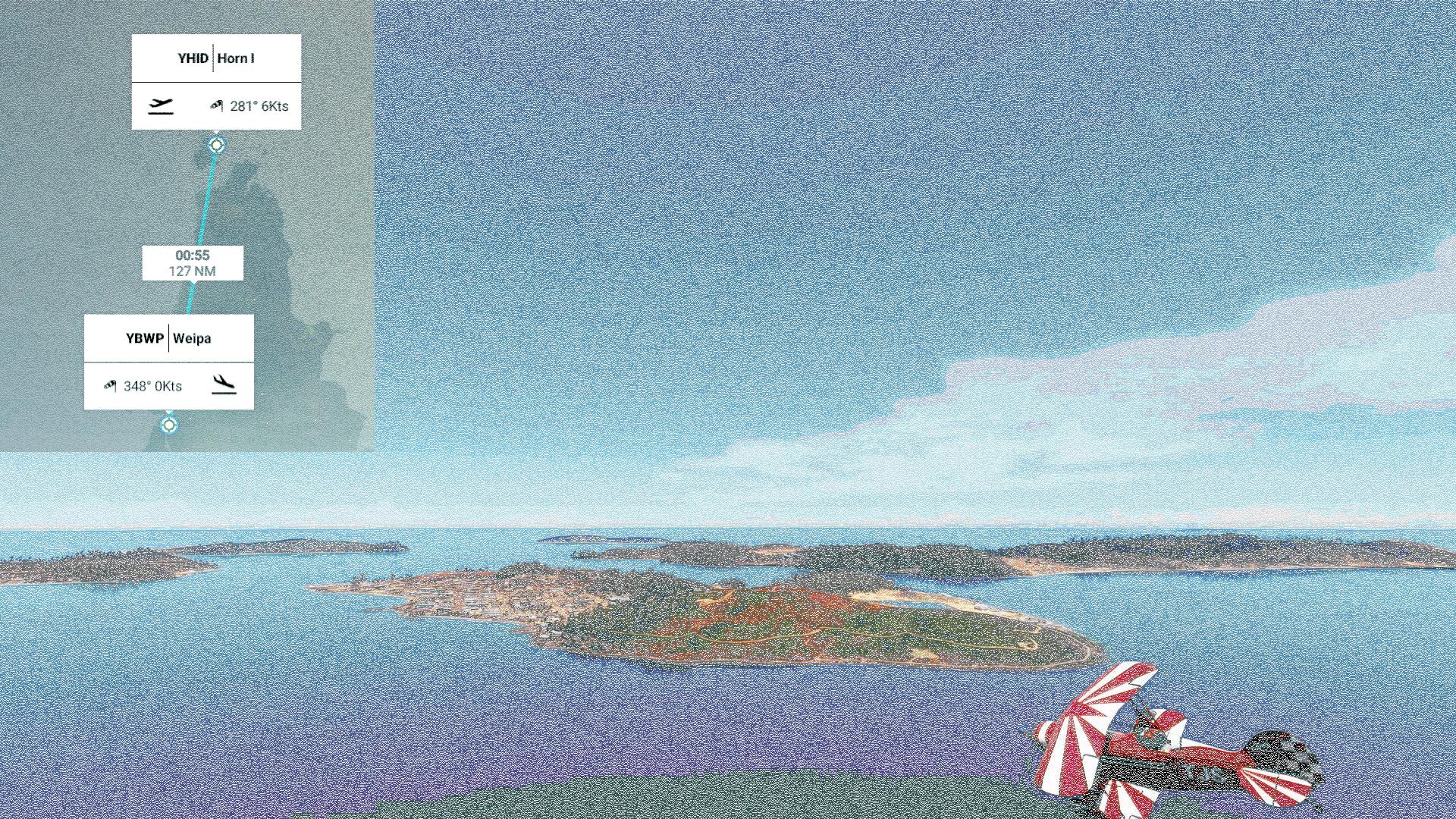

Today we're off to Weipa, home to the world's largest bauxite mine. Actually three mines. We'll be leaving the Torres Strait islands and heading down Cape York.

Cape York is mostly beaches.

Cape York is mostly beaches.

|

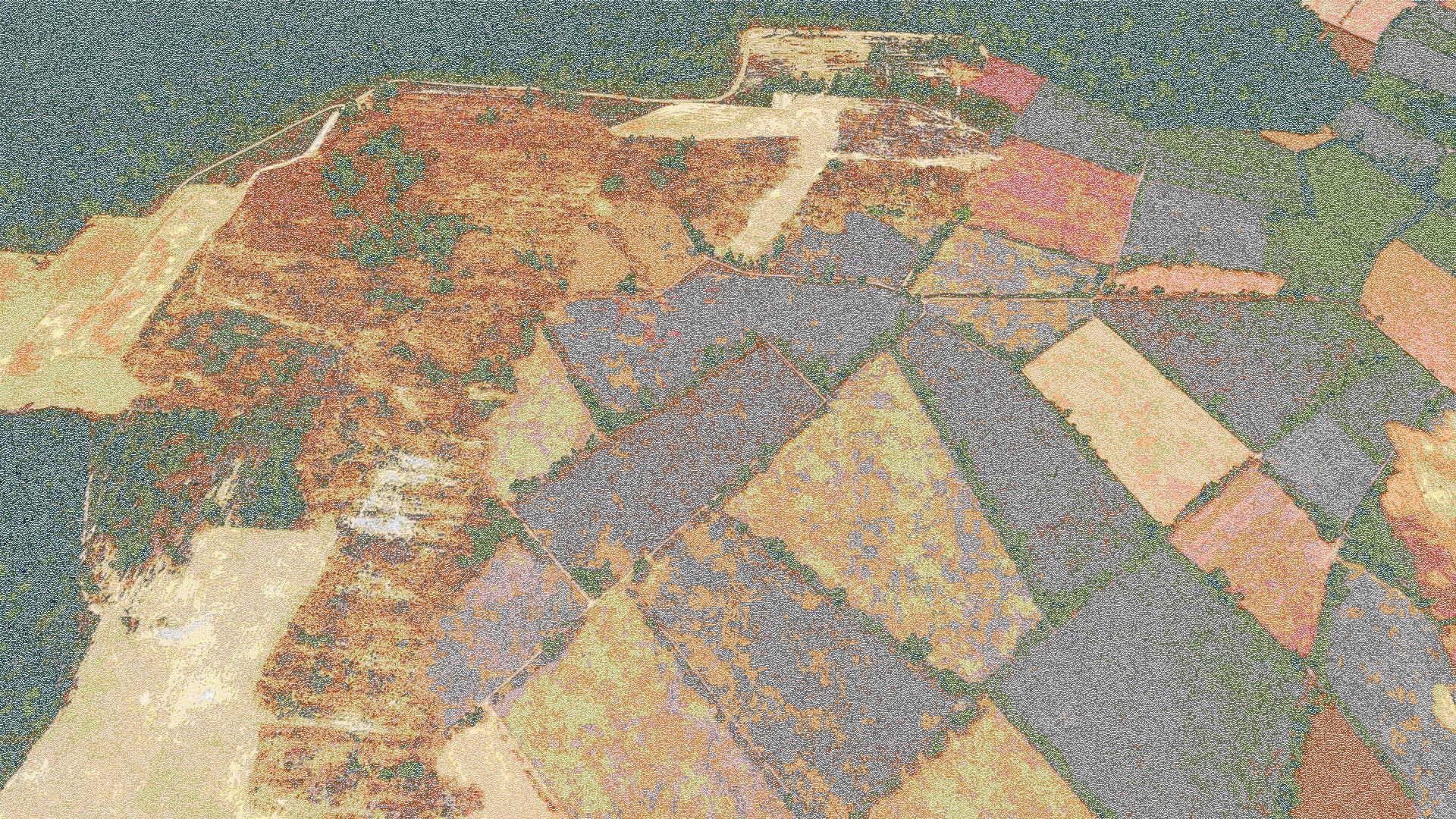

And strip mines. Bauxite mining is essentially stripping off the first few meters of sedimentary rock. And all of the vegetation, topsoil and critters too of course. Looks like they plant stuff on top when they're done. That's nice. You can hardly tell from up here.

And strip mines. Bauxite mining is essentially stripping off the first few meters of sedimentary rock. And all of the vegetation, topsoil and critters too of course. Looks like they plant stuff on top when they're done. That's nice. You can hardly tell from up here.

|

Pleasant looking place. Weipa. The town is what you might call bespoken; custom-built by the mine so the miners had a place to stay.

Pleasant looking place. Weipa. The town is what you might call bespoken; custom-built by the mine so the miners had a place to stay.

|

Well, that's it then. Time to go catch some barramundi.

Well, that's it then. Time to go catch some barramundi.

|