Gladstone

Queensland

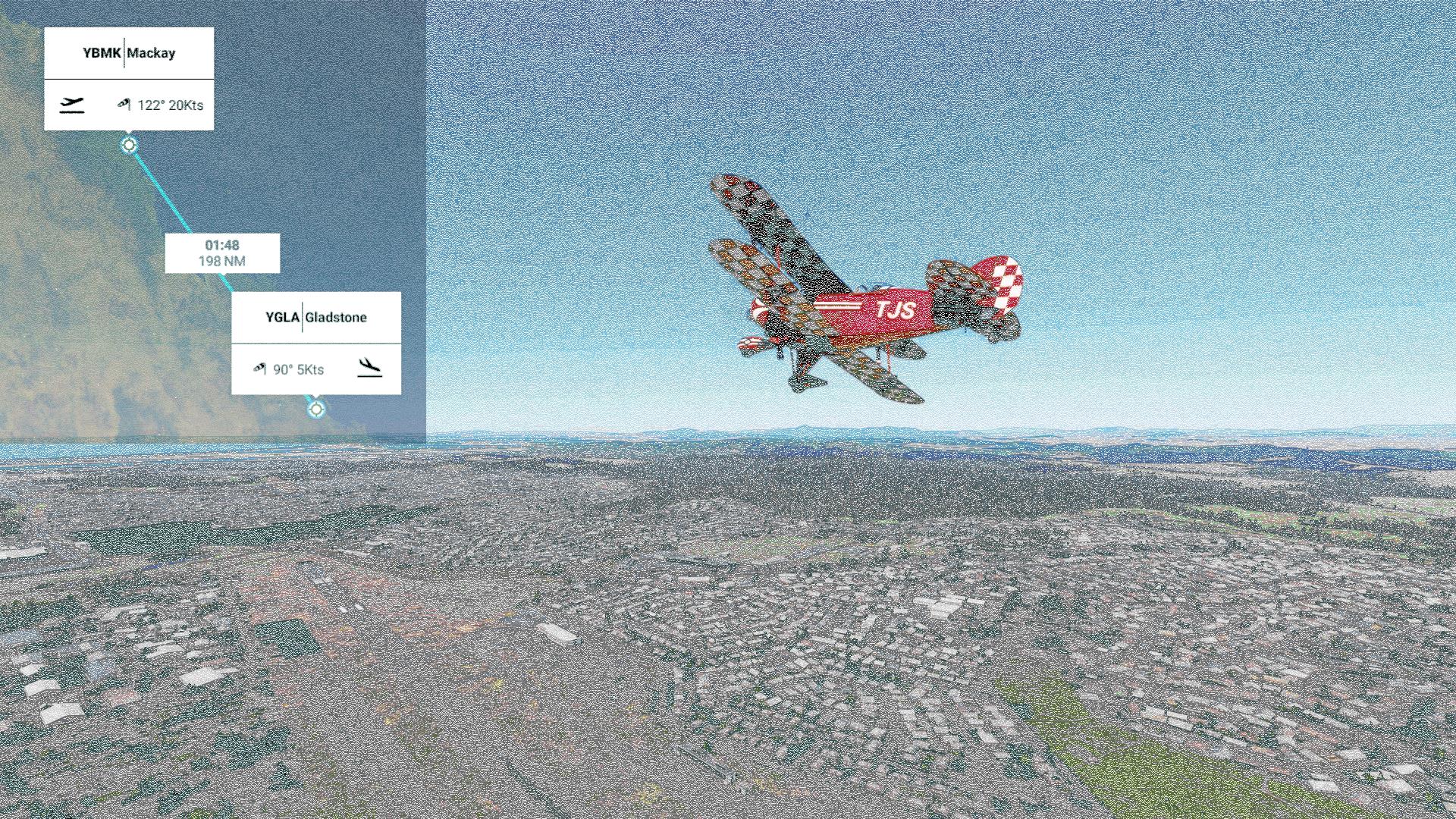

This morning we're off to Gladstone, one of the largest and most commercially successful ports in Australia. It is also on the Tropic of Capricorn, more or less, at 23.8 degrees south of the equator or at about the same latitude as Rio de Janeiro in Brazil. Probably a different vibe though. Gladstone is mostly industries like turning alumina into aluminum, and old tyres back into oil. But they do have a huge tourism industry, likely because their beaches are mostly safe.

Croc Country, which we've been in for some time now, ends at the Boyne river, just south of Gladstone. So while you can still get crocs in Gladstone they're approaching the edge of their range. You're more likely to find Crocodylus Porosus, or estuarine crocodiles, or saltwater crocodiles, or just plain salties, anywhere along the top bit of Australia, all of New Guinea, Malaysia, Indonesia and the Solomon Islands, and bits of the Phillipines, mainland Asia, India and Bangladesh. If you do run into a saltie it may be 70 years old. Don't try to outswim it; it can swim three times faster than an olympian. If you stay in shallow water to avoid the salties, be aware that a croc can remain hidden in knee-deep water for an hour. If you go far out to sea to avoid them then you should be aware that tagging and satellite tracking have shown crocs to travel great distances - 570 km - in open ocean, and they are smart enough to layover in a bay and wait for the winds and current to change in their favour. They recognize prey patterns. So if, while camping in croc country, you generally go to the creek near sundown to get water, eventually you'll have a saltie waiting for you. Their teeth are five inches long, and they clamp shut with a force of 3,700 pounds per square inch. A saltie can weigh a ton and yet propel himself out of the water with his enormous tail. In Queensland, there is generally one croc attack per year and one fatality every three years. And yet, if you swim in Queensland, and particularly around Gladstone, it's probably not a saltie that will get you. It'll be a stinger.

Irukandji Jellyfish, a little critter about the size of a loony, is a type of box jellyfish. If it stings you you will suffer excruciating pain, mostly in the lower back and abdomen; headache, nausea, vomiting, and a sense of impending doom. Probably because your brain is bleeding. And you generally don't even know you're swimming amongst these stingers because of their size. If you want to see what's attacking you, you want a Bluebottle.

The Bluebottle is a Pacific Man'o'War (Men'o'War?) siphonophore. Almost, but not quite, a jellyfish. More sort of a polyp commune where all the bits work together to sting things and then eat them. Since its not really critter, declaring one dead is a bit of a philosophical endeavour, and the upshot is a dead one can still sting you. While their sting is not as dangerous as that of the irukandji, it is still quite painful. A bluebottle can have a float (the bottle) of as much as 15 cm, and its stinging tentacles can be 10 meters long. As big as they are, though, the bluebottle is not overly dangerous. If you're after overly dangerous, then you are after the Chironex.

A chironex jellyfish can kill you in one minute. Their stingers can accelerate at 40,000 G - the fastest anything in the natural world bigger than a sub-atomic particle. So fast they can pierce crab shells. So fast that if they could maintain that acceleration for 12.74 minutes their stingers would be going the speed of light, but only from the stingers' point of view. From the point of view of the rest of the jellyfish here on Earth the stingers would only be able to approach, but never actually achieve, the speed of light. Still pretty impressive for a jellyfish though.

If stingers aren't your thing, consider a mollusc. There are two that may try to kill you while you swim in Queensland - the Blue Ringed Octopus, one of the world's most venomous animals (and it's really pretty), or possibly you may find a nice shell on the beach and it turns out to be a cone shell, the jab of which can cause intense pain, paralysis and death.

If you do manage to make it into the water without being eaten or poisoned, do try to avoid stepping on anything. The stonefish looks like a bit of the ocean bottom, maybe a rock. It is the most venomous fish there is. But not the most dangerous fish there is. For that you probably want one of the fifty species of shark that you are swimming with. While swimming in areas known to be frequented by sharks, it is vitally important to not swim after dusk or at night, when sharks are more likely to be feeding. And never swim alone. Always swim with someone who does not swim as fast as you do.

So you may have decided it would be better to simply stay on the beach. A wise decision. Just watch out for the other sunbathers sharing your beach. The red belly black snake loves a good sunny beach. If it bites, you won't be paralyzed: that's the good news. The bad news is that this snake and the brown snake both cause your blood to thin alarmingly, sometimes to the point of major leaks inside you. But you won't be paralyzed.

That's more of a tiger snake thing. If one of these bites you you're likely to experience "descending paralysis" - double vision, drooling, slurred speech, severe muscle pain and then cardiac arrest. Just like if a death adder or a coastal taipan gets you. In the case of a coastal taipan, though, you may not get the full experience because their bite is always and almost immediately fatal without medical intervention.

Maybe avoiding the beach is a good move too. Try a hike in the rainforest. Just make sure you wear long pants wherever you go. The paralysis tick will be out there somewhere and if he gets you, over the course of 48 hours, you will suffer weakness, lethargy, a lack of coordination, double vision and drooling. Unless you're allergic. Then you'll most likely die.

If you don't run into a tick in the woods there's always funnel web spiders. They like the forest too. While their bite is not often fatal, they do cause sweating, headaches, high heart rates and severe chest and nasal congestion.

Or you can stay away from the water, off the beach and out of the forest. You can simply stay in Gladstone. Maybe go to a restaurant. Just avoid any dark, dry, sheltered places and you probably won't run into the redback spider.

So off to Gladstone! The safest place on earth.

Some of the hills around here aren't really hills at all. There are hundreds of really old volcanoes in Australia, stretching some 3,500 km from Tasmania to Northern Queensland. And that's just the Cosgrove Tract. There are two other chains. Fortunately, none of the volcanoes on mainland Australia have erupted since the Europeans came, but stories of the indigenous people include tales of eruptions. Australian volcanoes are different from most other volcanoes in that Australia is smack on top of a stable tectonic plate, and so the normal ring-of-fire scenario is not at play here. It means that Australian volcanoes are deep-down things made by plumes from really way far down there. It might also mean that when the place blows it'll blow up real good. Australia has been drifting northwards over the millennia and the eastern part of the country is now over the world's largest chain of super volcanoes, stretching 2,000 km from the Whitsundays to Melbourne. We'll probably talk about this some more when we get to Melbourne, but for now, let's just say that this chain is 3 times the size of the Yellowstone super volcano which they say will be an extinction event when it goes.

Some of the hills around here aren't really hills at all. There are hundreds of really old volcanoes in Australia, stretching some 3,500 km from Tasmania to Northern Queensland. And that's just the Cosgrove Tract. There are two other chains. Fortunately, none of the volcanoes on mainland Australia have erupted since the Europeans came, but stories of the indigenous people include tales of eruptions. Australian volcanoes are different from most other volcanoes in that Australia is smack on top of a stable tectonic plate, and so the normal ring-of-fire scenario is not at play here. It means that Australian volcanoes are deep-down things made by plumes from really way far down there. It might also mean that when the place blows it'll blow up real good. Australia has been drifting northwards over the millennia and the eastern part of the country is now over the world's largest chain of super volcanoes, stretching 2,000 km from the Whitsundays to Melbourne. We'll probably talk about this some more when we get to Melbourne, but for now, let's just say that this chain is 3 times the size of the Yellowstone super volcano which they say will be an extinction event when it goes.

|

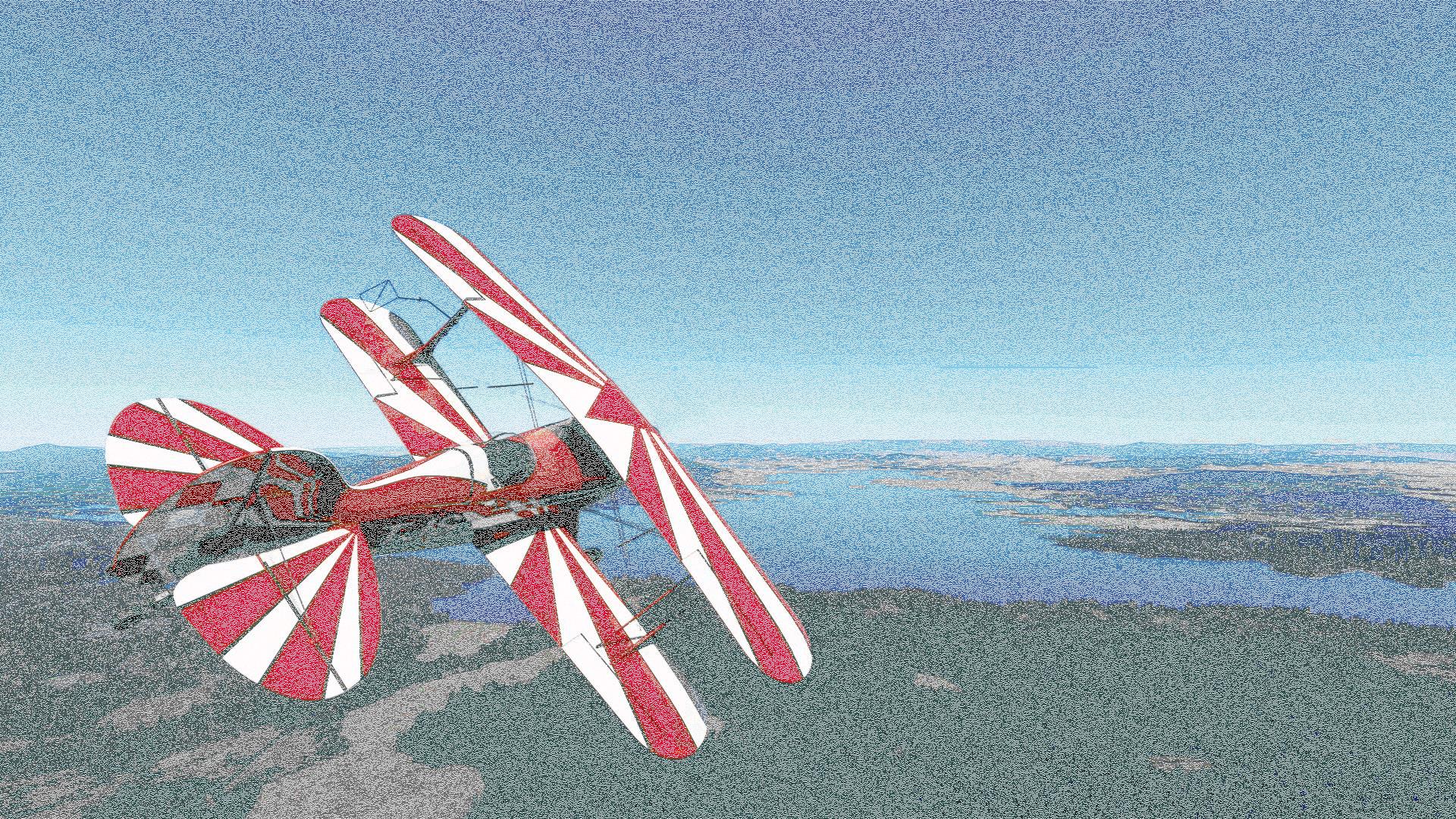

Awoonga Lake. They stock it with barramundi, and some guy caught one that weighed over 36 kg.

Awoonga Lake. They stock it with barramundi, and some guy caught one that weighed over 36 kg.

|

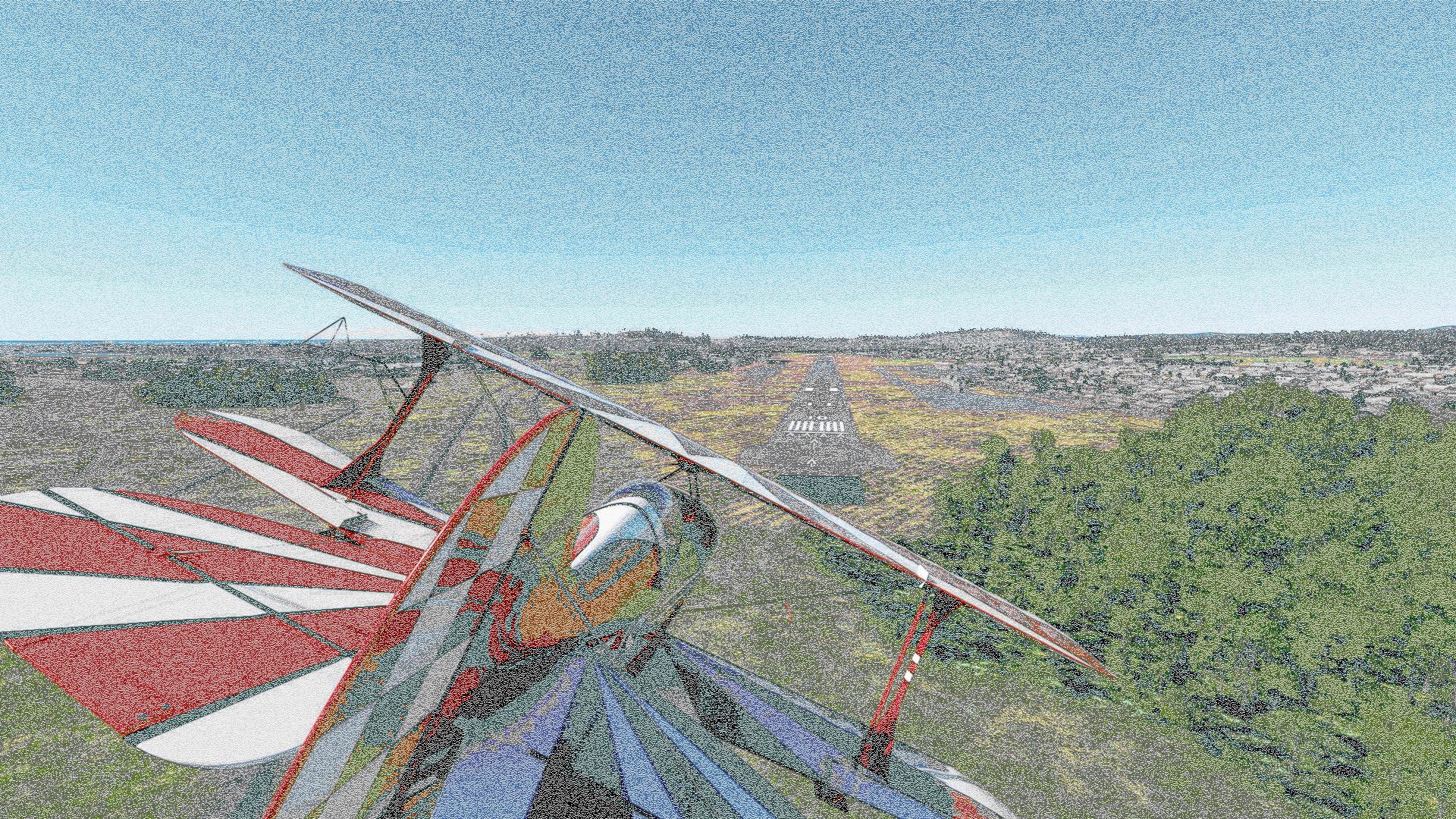

Well, here's our stop, Gladstone. I think we're just about within range for a lengthy flight that'll get us to Brisbane. See ya.

Well, here's our stop, Gladstone. I think we're just about within range for a lengthy flight that'll get us to Brisbane. See ya.

|