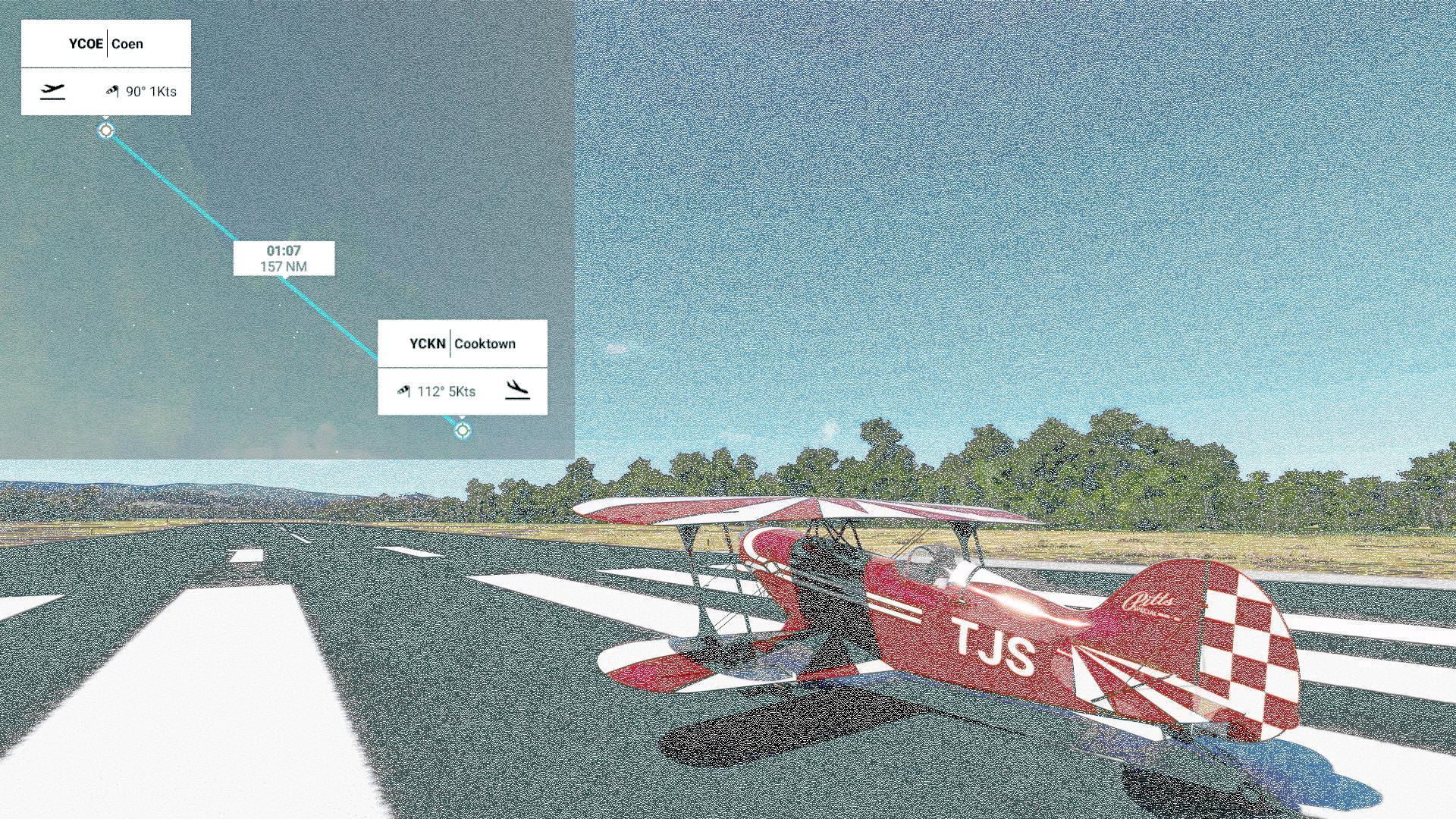

Cooktown

Queensland

The Cenozoic (New Life) Era began about 66 million years ago, some say when a comet struck the Earth. It's called the New Life Era because all of the Old Life died off. At about the same time that everything was dying in Australia, the island continent started drifting northwards quite quickly. About seven cm per year. And as it drifted, it found itself over different volcanic regions way deep down. This had a couple of consequences: one is that the eastern part of Australia started to rise a great deal, moving the drainage divide four hundred km inland and forming a mountain range. The other is that the previously temperate coast became tropical; corals started to form.

As the newly formed Great Dividing Range started to erode, it caused a great deal of sedimentation in the surrounding waters of the Coral Sea, ironically making the growth of corals difficult. So at the pace of coral growth (upwards of 3 cm per year) the corals started to spread outwards and away from the source of sedimentation.

Over the millenia, sea levels rose and fell. As the corals became exposed they would of course die off, but their skeletons would remain. Sedimentation continued from the Great Dividing Range, filling in the low spots in the Coral Sea. Then as the sea levels rose again, corals would resume building upon the skeletons of their ancestors, any new territory created by sediments, and any inundated islands. This process has been going on for at least 600,000 years off the east coast of Queensland from as far north as Bramble Cay, the northernmost point of land in Australia, all the way south to Lady Elliot Island, near Bundaberg, most of the way to New South Wales. A distance of almost two thousand kilometers, covering an area of almost 21,000 square km.

For the last 20,000 years, the sea level has been steadily rising, and is today some 120 meters higher than it was. But the dramatic rise in sea levels tapered off around 6,000 years ago. The structure of reefs, cays, lagoons and islands that constitute the Great Barrier Reef of north eastern Australia has been more or less stable in that time. Two hundred and fifty years ago, it was simply waiting for someone to consider it a barrier. Someone like Captain Cook.

James Cook was an able seaman and master's mate aboard the HMS Eagle in 1755. It was the eve of the Seven Years' War, the World War that predated the First World War by 158 years. The Eagle was patrolling for French ships. They captured one and sank another, and for his contributions, James Cook was promoted to boatswain. As a bos'n he couldn't actually command, but due the vagaries of war, found himself briefly in command of the small cutter Cruizer as it accompanied the Eagle.

Perhaps spurred on by this taste of power, he completed and passed his Master's in June of 1757, qualifying him to navigate and handle a ship of the King's fleet. After this he found himself serving onboard the Pembroke, capturing the Fortress of Louisbourg and laying siege to Québec in 1758. It was during this siege that he displayed a natural talent for surveying and cartography. He mapped the entrance to the St. Lawrence River to such a degree of accuracy as to allow General Wolfe to famously attack Québec on the Plains of Abraham.

After the war he put his talents to use in mapping the rugged coast of the New Found Land, and he also engaged in some scientific experiments. There was a solar eclipse on 5 August 1766. Cook took accurate timings of the event, and by comparing these with similar timings in England it was possible to calculate the longitude of the observation point in Newfoundland. The resulting maps were so accurate that they were still in use into the 20th century, two hundred years later. Master Cook continued his Newfoundland voyages for five years in total before returning home to the East End (of London).

But he didn't get much rest. In 1769 there was to be a transit of Venus across the sun. By using observations of the event at widely separated positions on the globe it would be possible to calculate the distance of the Earth to the Sun. So on 25 May 1768 the Admiralty commissioned the recently promoted Lieutenant Cook to head a scientific voyage to the Pacific to record the transit event from that location. He was given command of the HMS Endeavour, and departed England on 26 August 1768. They rounded Cape Horn and took the Drake Passage west, arriving in Tahiti on 13 April 1769, just in time for the observations of Venus.

At the completion of the observations, Cook opened his sealed orders and discovered the real purpose of the mission - to search the South Pacific for the fabled Terra Australis that was rumoured to exist "somewhere". For this new mission he enlisted the help of a talented Tahitian - Tupaia - who helped guide Cook through the Polynesian islands as far as New Zealand. While in New Zealand, of course, they mapped the coastline before heading west to see what was over in that direction. It turns out it was the southeastern coast of a new continent. I mean, it was new if you were British. Not if you were Dutch. But new to James Cook anyway.

On 23 April 1770 the Endeavour was off Bawley Point and observed "several people upon the Sea beach they appear'd to be of a very dark or black Colour...". And this was likely the first direct observations of indigenous Australians by a British ship. Less than a week later they made landfall at Stingray Bay, which Cook later renamed Botany Bay in reference to the unique things his two scientists, Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander, were finding there. While in Botany Bay he made contact with the local inhabitants, the Gweagal people, although they were somewhat coy.

Continuing north, Cook and the Endeavour put in at Bustard Bay, so named for the bustard bird they ate there, on 23 May. A week later they were at Thirsty Sound, where they found a lot of butterflies but no water. Cook and his crew didn't know it, of course, but they were at the very southern end of the largest reef system in the world, being some forty miles west of Lady Elliot Island. Leaving Thirsty Sound, ship and crew headed north again and smack into the Great Barrier Reef.

One June 10th they rounded Cape Tribulation. Cook would later write in his journal, "because here begun all our troubles.". The next night, a clear and moonless night, at just before 11:00 PM, the Endeavour ran aground on a reef and immediately took on water.

Not many knew how to swim back in those days. Certainly your average sailor would never learn how to swim. If you were swept overboard or for whatever other reason found yourself in the water it was better to go quick. No one was likely to help you. There were no life jackets or rings to throw to someone, and lifeboats would be a much later innovation. Any boats onboard would be safely stowed and not quickly accessible. So it was with a certain clarity of purpose that the sailors approached the task of manning the pumps. Everyone took their turn, including the captain.

The particular reef they had struck rose sharply from the depths. Soundings indicated that there was depth of perhaps twelve fathoms (seventy-two feet) less than a ship's length away. So it should have been a fairly straight forward task to free the vessel. A kedging anchor was set, and an attempt was made to pull the ship back into open water by hauling with a will on the chain. But she stuck fast. So the order was given to lighten her. Cook estimated that between 40 and 50 long tons of ballast, spoiled stores, drinking water, and even all but four of the guns were thrown overboard. On the next high tide another attempt was made to free her, which was again unsuccessful.

On the afternoon of June 12, the longboat was deployed with two large bower anchors, and block and tackle. There was to be one more attempt with the evening high tide. Meanwhile, the hole in her hull had worsened and she was taking on an alarming amount of water. This would certainly worsen if she were freed. Nonetheless, at 10:20 PM that evening, at high tide, she was freed and drawn off to deep water. And then everyone manned the pumps.

Pumps in the day were not the same as they are today. The shipbuilders in the age of the Endeavour did not have electric motors. They did not even have pipes. A pump in 1770 was two hollowed out Elm logs bound side by side, the lower end extending into the bottom of the bilges and the upper end exposed to the top deck. Through these two tubes ran a chain with leather buckets attached to it, and pulleys on either end allowed the chain to travel up the one and down the other bicycle chain style, the buckets scooping up water at the bottom and expelling it onto the deck at the top. The whole effort was driven by many men using a windlass, a winch-like device with no mechanical advantage. It was exhausting work. But no one complained, even when the ship's carpenter made a substantial mistake measuring the depth of water in the bilges and pronounced that they were doomed.

Though not imminently doomed, the Endeavour was still twenty-four miles from shore and sinking. The pumps were keeping ahead of the leak for the time being but that could change at any time. The three ship's boats on board were not lifeboats, they were more what you would consider tenders and certainly not of sufficient capacity for the entire crew. So midshipman Jonathon Monkhouse, who had some experience with such things, proposed fothering the ship. This involved sewing bits of oakum, wool, and even dung, into an old sail and hauling it under the keel where the injury was. The water pressure would force the sail and its load of garbage into the cracks and holes, thereby sealing the wound. And it worked.

With the fothering in place, there was only need of one pump. The Endeavour managed to limp northwards, finding safe harbour at what would be named Endeavour River. Through the use of the remaining kedging anchors, she was warped upriver against wind and careened, that is, run aground at high tide so as to expose the hull at low tide. With the hull thus exposed, it became apparent that there was a fist-sized lancet of coral that had punctured the hull and then broken off. It was this broken piece of coral embedded in the hull, covered in oakum and old sail, that had kept everyone alive.

The Endeavour remained careened for seven weeks while she was repaired, refitted and reprovisioned. During this time, the two scientists onboard made some amazing discoveries. For the first time, they saw crocodiles, dingoes, flying foxes, and any number of lizards, snakes, fish and insects. A mysterious animal was shot by Lt. Gore and then eaten by the officers and gentlemen. This was later identified as a ganguuru by the Guugu Yimithirr people when they chose to make contact.

The indigenous people met with Cook and his men five times, and relations were quite friendly. They seemed to be led by "a little old man".The Europeans learned, and more importantly, recorded, 130 words and phrases of the Guugu Yimithirr language. This was the first written record of an indigenous language in Australia. Things were going well with the ship and things were going well with the locals. And then the crew caught a large number of green turtles in the river to eat.

The Guugu Yimithirr were shocked that someone would take so many turtles at one time. They tried to persuade Cook to return at least some of the turtles. Cook and his men interpreted this as the natives attempting to steal the turtles. There was some violence, and Cook's camp was twice burned. A suckling pig was killed. Finally, Cook fired at the locals and wounded one. The indigenous people retreated and Cook chased them all the way to what is now called Reconciliation Rocks. There, accompanied by Banks and some others of the crew, Cook made signs of peace and returned some weapons that had been taken from the Indigenous people. Then, according to Banks, "We followd for near a mile, then meeting with some rocks from whence we might observe their motions we sat down and they did so too about 100 yards from us. The little old man now came forward to us carrying in his hand a lance without a point. He halted several times and as he stood employd himself in collecting the moisture from under his arm pit with his finger which he every time drew through his mouth. We beckond to him to come: he then spoke to the others who all laid their lances against a tree and leaving them came forwards likewise and soon came quite to us. ".

Shortly after this, the Endeavour was as repaired as it was likely to get, and Cook and his crew took their leave of the Endeavour River, the Endeavour Reef, and the Guugu Yimithirr. Today, at the sight of the beaching of the Endeavour, you will find the little town of Cookville. Let's go see.

Sort of a barren place inland. Let's go see the coast.

Sort of a barren place inland. Let's go see the coast.

|

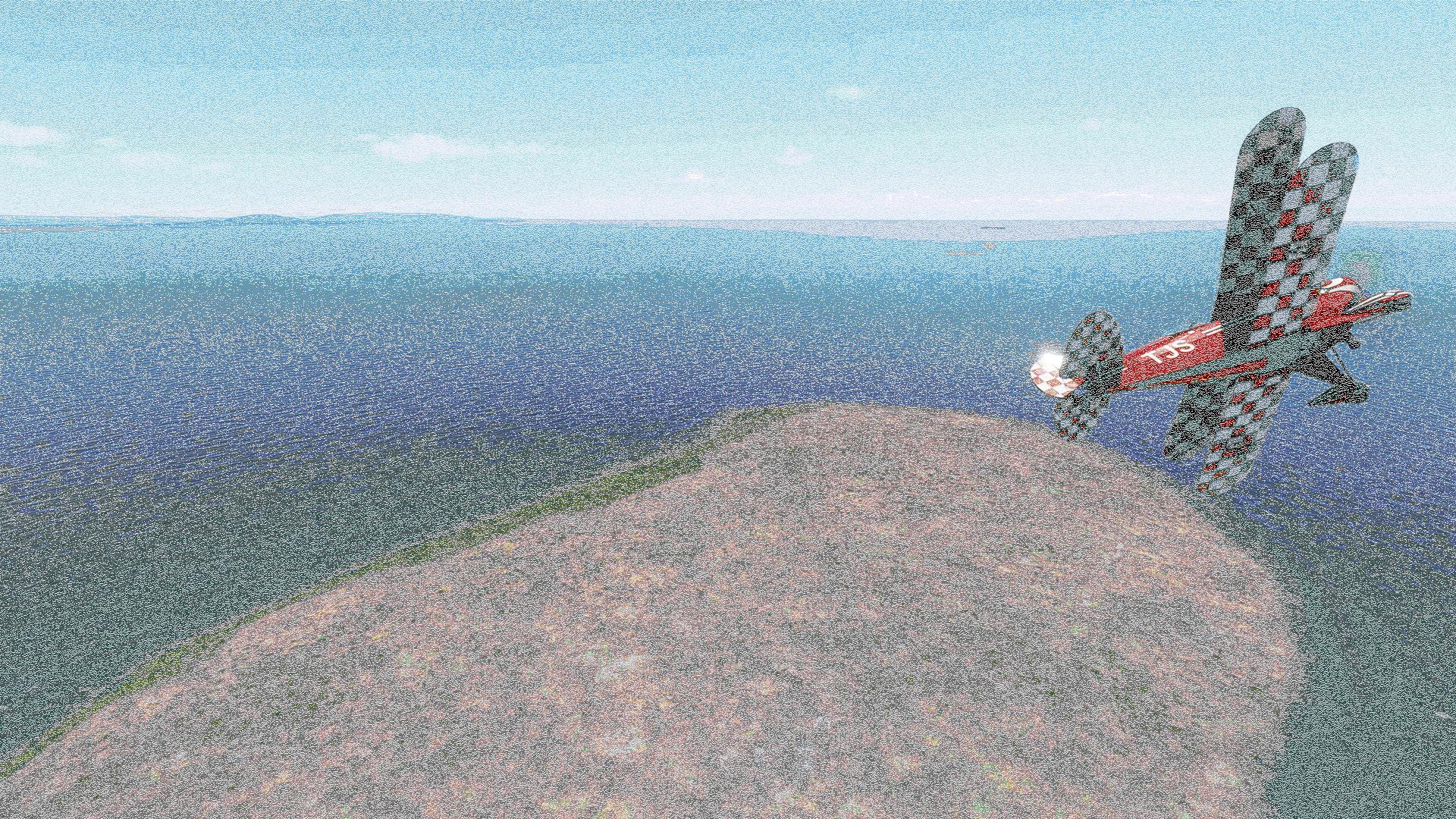

There are thousands upon thousands of these little islands all over the place. It must be about impossible to get a ship of any size through here.

|

|

Here's the mouth of the Endeavour River where Cook beached.

Here's the mouth of the Endeavour River where Cook beached.

|

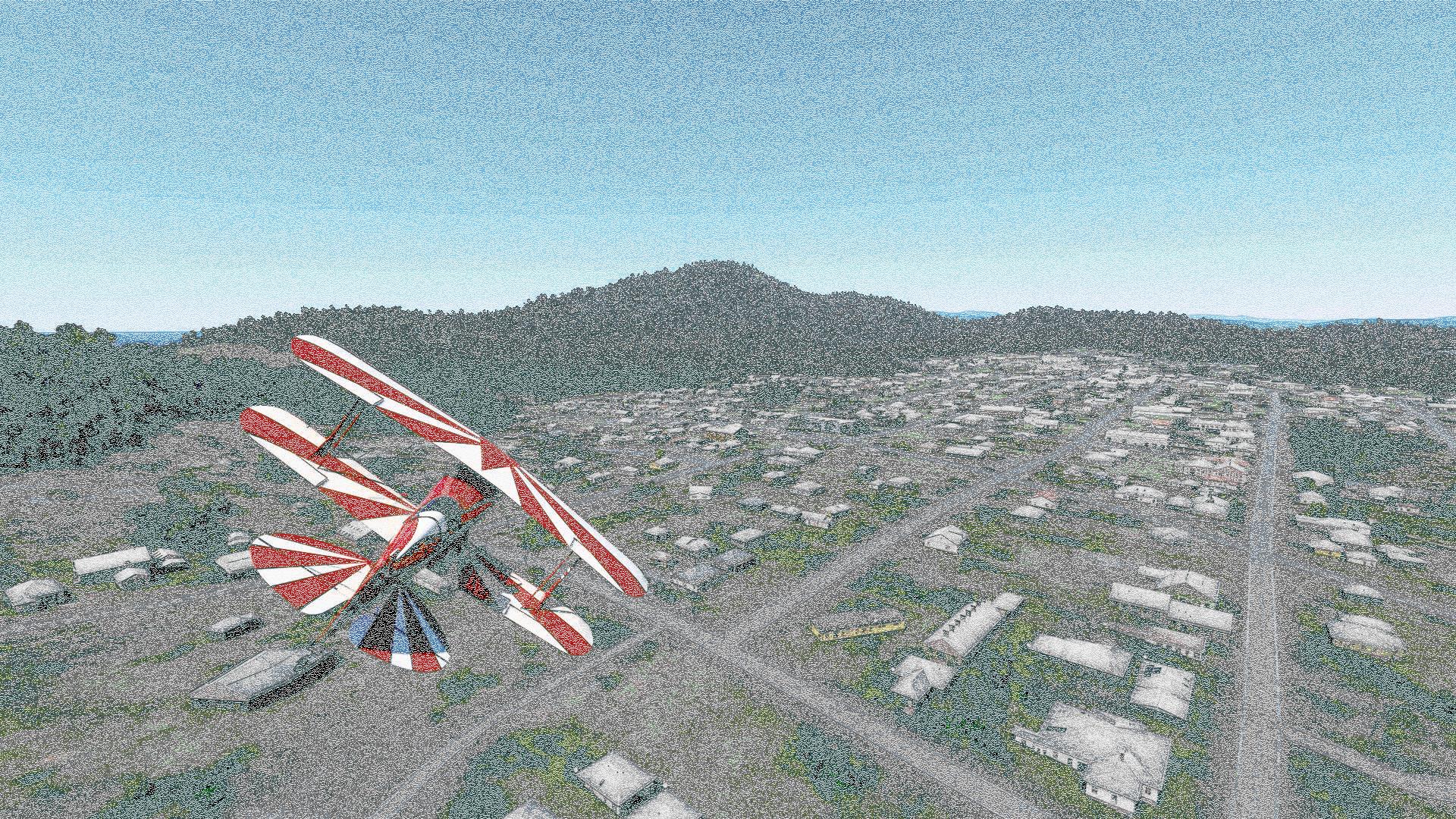

Here we are, the little town of Cooktown. Recently, the town has been the scene of a ghastly murder. The police think the killer was someone local, so there are 2,631 suspects.

Here we are, the little town of Cooktown. Recently, the town has been the scene of a ghastly murder. The police think the killer was someone local, so there are 2,631 suspects.

|

So here we are for the night. We didn't have to beach the plane after all. Tomorrow we'll go meet the shy and elusive Bogan people of Cairns. There are a lot of Bogans in Cairns, I am led to believe.

|

|