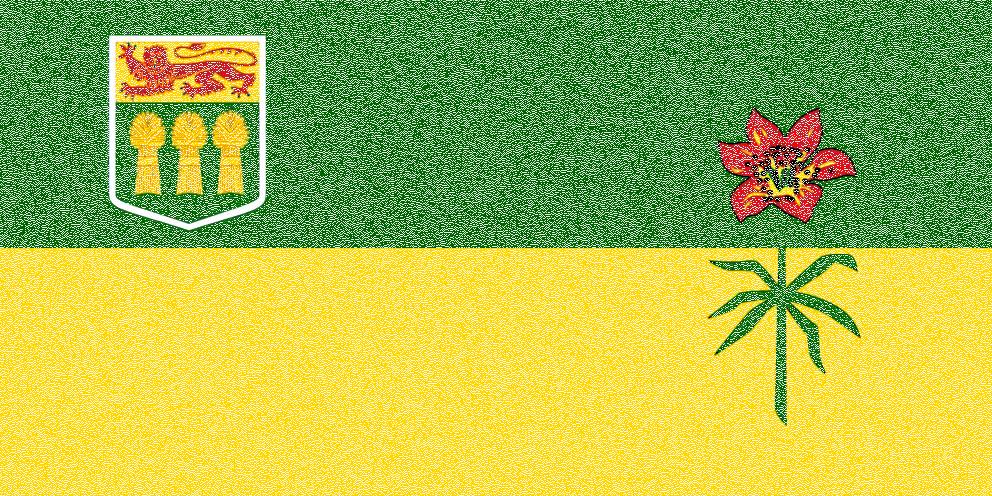

Saskatchewan

Land of the Living Skies

The story so far...

So in 1866 there was no Canada, just a few colonies within British North America. To the far east there was Newfoundland. Labrador had been a part of the New Founde Lande since 1809, although the exact border between it and Canada East varied upon whether you asked the question in English or in French. Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and PEI were pretty much as we know them today. Canada East, which had been called Lower Canada until 1841, covered the southern region of what we would call Québec. Canada West, Upper Canada until 1841, covered the southern bits of what we would call Ontario. Canada West effectively ended at Fort William at the far end of Lake Superior. Then, after quite a bit of rocks and trees and water there was a little colony around the Red River. Then a large quantity of nothing until you hit New Caledonia, or New Georgia on some maps, either way renamed British Columbia in 1858. To the extreme west of that colony there was an island that was home to the tiny town of Victoria, which is where all of the well heeled, and therefore the decision makers, lived. The bulk of the Terra Incognita between Labrador and British Columbia, and stretching north to the British Arctic, was Rupert's Land, ceded to and under the control of the Hudson's Bay Company.

To the south, our neighbours had just finished their civil war, which ran for four years from 1861 to 1865. British North America had been involved to a surprising degree in this war - as many as 55,000 volunteers from the colonies enlisted (including Calixa Lavalée, who would compose the music for O Canada), largely fighting for the Union side to the north. There were close economic and familial ties across the border, and the North was opposed to slavery, as were the BNA colonists. British North America had become the north end of the underground railroad and accepted a large number of fleeing slaves into communities such as Shanty Bay on Lake Simcoe.

But there were some Confederate sympathies as well, and a few hundred volunteers went south. Britain itself was undecided about whom to support in the war, and in order to help them decide, the South sent two envoys across the Atlantic to discuss their right to be recognized by Britain and France. The British mail packet RMS Trent, upon which the envoys were passengers, was intercepted by the USS San Jacinto, the envoys were captured, and a diplomatic crisis ensued. This could easily have resulted in Britain entering the war on the side of the South, so the North backed down and released the prisoners. Meanwhile, British forces were strengthened within the colonies.

Of course, Britain, and so therefore the colonies of British North America, were officially neutral. This meant quite a lot of war profiteering. The CSS Alabama was commisioned by the South and was built near Liverpool, England. In its two years of attacking Union ships it never once docked in a Southern port. And on this side of the ocean, the struggle for the South to remain independant from the North struck a chord with maritimers who wanted to remain independent from the Province of Canada, which was becoming the center of power in British North America. The Maritimes, and in particular Halifax, became a base of operations for Confederates circumventing and harrying the North's blockade, for which the South paid in cotton, which could then be sold to Britain indirectly, without breaking any of war's delicate etiquettes.

But the Confederate agents often overstepped the bounds of decorum. In 1864, Montréal was a base for one such group. They crossed the border into Vermont, where they robbed the bank at St. Albans, killing a citizen and running off back to Canada with $175,000. They were pursued across the border by Union forces, causing another international incident. This incident was not helped any when, after their capture by Canadian forces, the judge ruled the Confederates to be engaged in an authorized act of war, rather than a felony, and so therefore they were not subject to extradition.

And neither were the deserters and draft dodgers, some 15,000 of whom ended up this side of the border during the war and were made welcome. And so, by 1866, while the war had been over south of the border for a year, there were still some unresolved issues between the soon-to-be Canada and the States. Like the Irish. 150,000 of them called the States home, many so recently that they were not yet citizens. But nonetheless many of them had fought and died for the Union during the war. And while you could say that the Union was not overly fond of the British, that was nothing compared to the recent Na hÉireannaigh immigrants. Most of them, of course, were simply immigrants looking for a peaceful new home free from the troubles. But at least 10,000 Irish immigrants brought the troubles with them to America.

The Fenians, named after the Fianna Éireann, ancient Irish warriors, were a secret society violently in favour of an Irish Catholic Republic, and violently opposed to all things British. They were outlawed and brutally repressed in Britain, where they were known as the Irish Republican Brotherhood. But in the Land of the Free, where many of them were decorated war heros of the Civil War, their anti British sentiments were very much tolerated. So they thrived. Eventually they set their sights on a somewhat easy British target north of the border. Their intent was to take over British North American territory and use it as leverage to force Britain to give Ireland her independence.

Canada did not have a spy agency at the time. In fact the Dominion of Canada itself was a year away. But nonetheless it did have spies. They were already in place in the northern States looking for Confederate trouble (or possibly Union trouble), the American civil war being only just over. So with the rise of the Fenian Brotherhood, the spies were asked to be on the lookout for trouble from that quarter too. They infiltrated many of the Brotherhood's headquarters, an easy thing to do if you were Irish Catholic, and so gave advance warning of the impending attacks. In March of 1866 the Fenians were clearly up to something, so 14,000 volunteers were called up for active duty in British North America. When nothing seemed to be happening, they were stood down but were still in a state of readiness. So when the Fenian attack of Campobello Island in New Brunswick finally came in April of 1866, we were mostly prepared and the invaders only managed to destroy a few buildings.

But they weren't done. The next month they planned strikes in Canada West and Canada East but were foiled by four things: not enough militants signed up in Buffalo, Cleveland and Chicago; the Great Lakes were between the States and Canada at the intended invasion points and the invaders lacked sufficient boats; Canada mobilized over twenty thousand volunteers and thirteen steamboats to patrol the lakes; and lastly, but not to be overlooked, the States itself was growing a little concerned about harbouring a terrorist organization intending to overthrow the neighbours and arrested some leaders.

So the planned invasions of April and May didn't go according to plan. But in June there was a more determined effort to take the Welland Canal, the only way between Lake Ontario and Lake Erie by ship, and so therefore of immense strategic importance. 1,000 heavily armed Fenians, led by John O'Neill, a US Cavalry officer, marched into the undefended town of Fort Erie, about eighteen miles to the east of Port Colbourne, which was and is the Erie end of the canal, and captured it without firing a shot. They cut the telegraph lines and took over the bakery and hotel, and then commenced building fortifications for the inevitable response.

That response was swift. Within hours of the invasion, 900 men of the Queen's Own Rifles and the 13th Battalion along with 22,000 militia and the York and Caledonia Rifle Companies were amassed at Dunville, about eighteen miles to the west of Port Colbourne, and therefore 36 miles from the enemy forces. A great many other militia were in readiness, such as the 35th Battalion out of Barrie on the shores of Lake Simcoe. It was composed of volunteers like the young farm boy Sam Steele, who was amongst the very first to volunteer when he heard there was going to be trouble.

Meanwhile, 850 rifles under Lieutenant-Colonel Alfred Booker were deployed from Dunville to Port Colbourne, roughly half way between the opposing armies. Then the next day, Booker was ordered to march on Fort Erie. He was ordered not to engage the enemy but form up with an advancing column under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel George Peacocke. He got about half way, to a little place called Ridgeway, where it was discovered that the Fenians had also been advancing. Then, against orders, battle was joined.

The Canadians were not battle hardened, to put it gently. Whereas the Fenians were all Civil War veterans. The Canadians lacked such basics as food, water and sufficient ammunition, and only half of them had ever fired their new rifles before. As for leadership: Booker's troops were liberally sprinkled with Orangemen, who would have had their own ideas about the chain of command and marching past a group of Fenians without engaging. And tragically, Booker mistook Fenian scouts on horseback for a cavalry charge and formed his troops up to defend against horse, whereas the attack came on foot. When he ordered a change in formation under fire his mostly green troops panicked.

All in all, the Battle of Ridgeway and its subsequent engagements were a stunning failure, even though we technically won. With odds approaching 25:1 against, the Fenians would have simply run out of bullets at some point even if they met no resistance and could not possibly have won. They withdrew to the States, were arrested and then promptly paroled, as they really hadn't broken any American laws.

After hostilities, when the prisoners were swapped, captured Fenians returned to the States to much fanfare amongst the Irish. O'Neill himself was hailed as a hero, made Inspector-General of the Fenian Army, and led several more ill-fated expeditions into Canada against an increasingly organized defence. Lessons were learned at Ridgeway.

Meanwhile, Confederation took place on July 1st, 1867. Rupert's Land was purchased for one and a half million dollars two years later and the vast tract of land that it represented needed to be integrated into Québec, Ontario, and, by 1870, the brand new province of Manitoba. Louis Riel and his Red River Rebellion had been succesfull in negotiating the entrance of the Red River Colony into Confederation, but in the process he had angered the Orange Order, an organization that heavily influenced the government of Ontario and even the PMO. Even though he was elected three times to the House of Commons, Louis could never take his seat for fear of the Order. He had to surreptitiously arrive at the Parliament Buildings to sign the register, a formal necessity to retain ones seat, and then steal away into the night before he was recognized. He was essentially under a death sentence, in that officially the Federal government had no issue with him, but in reality, the Orange Order, which was the not-so-very-secret society which controlled the country, wanted him dead.

So, in the binary world of the Troubles, that made him a Fenian. In October 1871, John O'Neill and 40 Fenian soldiers crossed the border into Emerson, Manitoba, to talk to Riel and drum up support for the Catholic cause. Of course, Louis was neither Fenian nor Orange; he was Métis, Manitoban, and, in spite of what the Orange Lodge would tell you, Canadian. So he raised volunteers to send O'Neill packing; the Fenian Inspector-General was arrested in the States and that was the end of the Fenian troubles in Canada. But not the end of Louis Riel's troubles.

MacDonald, the PM, was Orange and so therefore couldn't anger the Order in Ontario by granting Riel a pardon. But he was also the PM, and so he couldn't anger the mostly Catholic Québecois by having him executed. And he was facing the Pacific Scandal, which we'll talk about another day; all with an election coming up. So he offered Riel a thousand dollars and a further six hundred pounds for his family if he simply buggered off. Riel obliged, aided in his decision by the approach of Colonel Garnet Wolseley on his "mission of peace".

The story continues...

The Pacific Scandal worsened; by 1874 it had resulted in the resignation of the Conservatives and the new PM, the Liberal Alexander Mackenzie, was not a member of the Orange Order. He had no particular axe to grind over the Red River troubles and so arranged amnesty for Louis, on condition that he remain in exile for five years. This suited Louis fine; he moved to Montana, married a girl, had children and became a teacher.

Meanwhile, the land west of the new Province of Manitoba, all the way to British Columbia, was the somewhat vacant North-West Territories. The territory was partitioned up into several districts, two of which, the District of Saskatchewan and the District of Assiniboia, bordered the postage-stamp sized Manitoba immediately to its west. Spurred on by the advancing white settlers and the retreating buffalo, Métis from the Red River were spreading into these districts. As the buffalo continued to disappear, they turned to a farming lifestyle, based on the French signeurial layout, which was a series of skinny strips of land with frontage on a river, so each strip, worked by one family, had access to water.

But the wave of white settlers was also expanding west. All through the 1870s plans were being made for a country-wide railroad, an unheard-of feat of engineering at the time, crossing the Shield in Ontario and the Rockies in British Columbia, both enormous challenges. But nonetheless it was going to happen, and in advance of its arrival, the Dominion survey teams arrived to impose order upon the vacant land of Saskatchewan and Assiniboia. And the order they imposed was the British Township system, basically giant squares of land. These townships were then sub-divided up into square mile sections, or concessions, and, more to the point, quarter sections of 160 acres. These quarter sections were made available to any and all of white European descent as homesteads.

In order to qualify for a mostly free grant of land, one had to register their intent to homestead for ten dollars with the people of the Dominion Lands Act. Initially you had to be a male of 21 years of age to apply, but to encourage immigration this was dropped to 18, and then even women could apply if they could prove they were the sole head of the family. There was always the understanding that you would be white and European, but this was better formalized later on by stipulating that you had to be either a British citizen or in the process of becoming one.

Once you had registered your homestead, then you had a sort of rental agreement to the land for three years. During that time, you had to Prove Up the homestead; you had to cultivate and reside on the land for the three years, after which time you would receive Patent (title) to the land. Even if your square of land happened to encompass some long, skinny strips of land that the Métis were squatting on, without title, since they hadn't followed the rules. This is what the inhabitants of St. Louis discovered in 1883 when their entire town, including a church and a school, and home to 36 families, was sold out from under them.

And then there were also the Plains Indigenous nations - Cree, Siksika, and even Lakota from the south under the leadership of Tatanka Iyotake, Buffalo Bull Who Sits Down, or simply Sitting Bull. The Lakota had fled to the Cypress Hills in the District of Assiniboia from the States to escape the US Cavalry, who were anxious to avenge General Custer and the Battle of Little Bighorn. The Lakota, and all of the rest of the Plains people were here following the buffalo, and, as the buffalo herds began to fail, they were all starving. But they weren't going anywhere. Just as Custer had had his last stand at Little Bighorn, the Lakota and all the rest were having their last stand against white settlers, and their stand was to be here, to the west of Manitoba.

So the existing population of the plains were not fond of the new white settlers. But those white settlers weren't having it all their own way either. The coming railroad was to span from ocean to ocean, passing right across the prairies from Winnipeg to Fort Edmonton. Land along this proposed line was suddenly quite valuable, and so that is where the new settlers had their homesteads. Once you proved up your homestead it was yours, and many people had full intentions of selling the land once towns and stations began to spring up around their land, at a huge profit. So even though severe droughts and even plagues of locusts were making the actual crops on their homesteads unprofitable, many immigrants arrived and set about homesteading on the eventual route of the Canadian Pacific Railroad, through the north country to the west of the Red River. But then their plans, and the railroad, went south.

Corruption was so endemic with the building of the Canadian Pacific Railroad that it wasn't even considered corruption; it was written into the contract. Large tracts of land were to be given to the railroad along the eventual route in order to build sidings and stations, far more land then they could ever possibly use. It was understood that they would sell the rest. In addition to the land written into the contract, those in charge had advance knowledge of and last-minute veto power over any routes or locations of stations, and so therefore towns. Land in these future new towns could be homesteaded in advance essentially for free and then sold at levels of profit that would make Croesus blush. So when all the legitimate homesteaders went north, the land speculators of the CPR, armed with better knowledge, and teams of hired "homesteaders", went south. There was outrage amongst all of the white settlers.

So this is the powder keg that was the land destined to become Saskatchewan, in the summer of 1884. The Plains Indigenous folks were angry because they were starving and the government was ignoring them, and the treaties they had signed, in order to expand Canada's sovereignty westwards. The French Métis, who had never signed a treaty, were utterly ignored, and quite angry. Anglo-Métis, or the "country born", and just plain Anglo folks were also finding the government unresponsive to sort out the various messes that were brought about by civilization moving west, such as the monopoly the railroad enjoyed transporting wheat one way and farm machinery the other. Everyone was angry at everyone else, but mostly they were all angry at the Canadian government.

Meetings were being held in various locations by various peoples to determine what to do about this. One such meeting, at the home of Abraham Montour, was held by Gabriel Dumont. Gabriel was quite a colourful character. Born in the Red River region, he rose to prominence within the Métis community becoming the defacto, if not in fact de rigeur, leader of the plains Métis. He first proved himself in battle against the Sioux at the tender age of 13, and he rose in the Métis "army" to become its adjutant-general. By 1863 he was elected Hunt Chief of the Saskatchewan Métis, a hopeless job because the buffalo had all but disappeared. Nonetheless, he implemented the Rules of the Buffalo Hunt, and fined any Métis who broke the rules, an unpopular but necessary strategy to attempt some form of conservation. But those who received fines complained to the local HBC Factor, Lawrence Clarke. By the time these concerns made it to the Lieutenant Governor it appeared that the Saskatchewan Métis were in open revolt against the government of Canada, who sent in the newly formed North-West Mounted Police. We'll talk much more about them later, but for today, they restored order quite quickly by essentially disbanding Dumont's Council of St. Laurent, of which council he was president. The council had no more power, but retained its voice, which it used to petition Ottawa to recognize the traditional land tenure of the Métis in Saskatchewan. But, being Métis, and even worse, French Métis, they did not even warrant a response. So Gabriel decided that a more direct approach to the issues was required. Thus it was that in March of 1884, in the home of Abraham Montour, the Council of St. Laurent decided that Dumont and three of his closest friends should travel to St. Peter's Jesuit Mission across the border and convince one of its teachers, a middle-aged Louis Riel, to accompany them north to help sort out the mess that was the North-West.

And so it was that one year later, in March of 1885, Riel, Dumont and several others set up the Provisional Government of Saskatchewan, in order to recreate the successes Riel had had with his Provisional Government of Assiniboia sixteen years earlier. But this was a vastly different dominion, and a vastly different Louis Riel. Sixteen years earlier he had been a handsome, articulate, well educated statesman. Now, in addition to all of that, he was on a mission from God as His appointed prophet. This tended to alienate him from the Catholic church, who viewed his extreme views as madness at best, and blasphemy at worst. Alienation from the church made him also alienated from many of the Plains peoples, who were being proselytized by Father Albert Lacombe. And the increasingly Protestant English population had no use for a French Métis leader who also wanted to be a Catholic prophet. Amongst the Métis, broadly speaking, the older Métis remembered Riel fondly from the Red River days and were on his side. But the younger Métis wanted no part of a rebellion or of a crazy Riel.

So when the swift federal response came to Riel and his rebel government, Dumont, his adjutant, had fewer than 200 warriors under his command to meet the challenge of the Prince Albert Volunteers under the command of the NWMP. They still managed to win the Battle of Duck Lake, mostly because the Canadian forces numbered less than half of Dumont's. But this was the age of the railroad; within a few short weeks, thousands upon thousands of reinforcements along with five hundred police swarmed into the area. But these forces found themseleves battling not one adversary on one front, but three: the Métis under the figurehead of Louis Riel (but the actual leadership of Dumont); the Plains People (Cree, Kainai, Piikani, Saulteaux and Siksika) under a loose confederacy led by Mistahimaskwa Big Bear of the Cree and Isapo-muxika Crowfoot of the Siksika; and of course the white settlers, who had no particular leader but had a voice in government.

Absent from this list of players was Tatanka Iyotake along with his band of Hunkpapa Lakota Sioux. They had been talked out of rebelling by the NWMP with promises of protection from the U.S. army, who were still bent on revenge for Custer. The Lakota Sioux complied, but the Federal Government's policy of starving indigenous peoples into relocating away from settlers convinced Sitting Bull and his people to take their chances south of the border. At least south of the border the Buffalo, which were stopped from migrating north due to fires deliberately set by Americans to keep them in the States, would be available for hunting.

There were several battles over the next few months. Some were won by Métis; some were won by plains people. Most were won by the Dominion. Finally, on June 3rd, 1885, Major Sam Steele of the NWMP defeated Big Bear and his Cree at the Battle of Loon Lake. Louis Riel and Dumont had been defeated the previous month at the Battle of Batoche. The white settlers, who had not been physical combatants, continued legal means of getting their concerns heard, and that would bear fruit many years later under the name of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, which we'll talk about another day.

So the Dominion inevitably won. The advent of the railroad meant that troops and police could be relocated anywhere across the breadth of the nation in weeks rather than months. Since the Dominion won, the affair is known as The North-West Uprising or the North-West Rebellion, rather than the North-West Resistance. And the leaders of the losing forces were inevitably punished. During the fighting, Battleford had been looted by indigenous people, and unfortunately they burned the house of one Charles Rouleau to the ground, who happened to be the Stipendiary Magistrate for the area. According to the December 14th, 1885 Saskatchewan Herald, "He [Rouleau] is reported to have threatened that every Indian and Half-breed and rebel brought before him after the insurrection was suppressed, would be sent to the gallows if possible." Non-English speakers were not given a translation of the events at trial; they were simply hanged. Eight of them.

Meanwhile, the trial of Louis Riel had been going on in Regina for some months. It was supposed to have taken place in Winnipeg where there would have been an even mix of Riel supporters and haters. But unfortunately for Riel, Sir John A. Macdonald was back in power, and that meant the Orange Order had some clout at the federal level and still wanted revenge for the Thomas Scott affair. So the trial for High Treason was convened in Regina before a jury of six Anglo Protestants. Louis still had supporters in the Québecois, who hailed him as a cult hero for the French cause. He also had Métis supporters, but they of course had no say. And Riel himself had no money, so he relied on French supporters for his legal expenses. His legal team had no particular use for the Métis, they simply wanted Riel alive as a French hero. So they worked up an insanity defence, pointing to Riel's time in various asylums in Québec and the visions he had been tormented with. The prosecution, of course, did not believe Riel to be insane, merely a traitor. It was Louis himself who broke the tie, giving two eloquent oratories, defending his actions and affirming the rights of the Métis. The eloquence of these speeches confirmed in everyone's mind that Louis was not insane, and so therefore he was sentenced to be hanged for high treason. But even though the jury found him guilty, they pled for leniency. As one juror later stated, "We tried Riel for treason. And he was hanged for the murder of Scott." Repeated attempts at a retrial, commuted sentence and leniency from the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council of Britain were denied. As far as the Prime Minister was concerned, "He shall hang though every dog in Quebec bark in his favour."

And so Louis Riel was hanged for the crime of High Treason on November 16th, 1885 at the NWMP Police barracks in Regina. It took four minutes to take his life but his legacy continues: he has been something of a tangible edge to the knifepoint separating English and French in this country.

Some time later, and as something of an anti-climax, on September 1st, 1905, the Saskatchewan Act and the Alberta Act carved those two provinces out of the NWT. The two had wanted to become just the one large province of Saskatchewan, but those in power at the time felt this would make too large and powerful a block. And there was always the fact that Alberta was something of a made-up province; its people had no particular claim to anythng other than their homesteads, so by hiving off half of Saskatchewan and calling it Alberta, the Dominion could retain ownership of all natural resources. But more on that another day. For today, we're off to Saskatchewan.